Col. Henry S. Olcott was sitting in the rustic dining room of an isolated farmhouse in Chittenden, Vermont when he spotted the answer to his midlife crisis. The owners of the farm held seances nightly, and among those arriving that day to gawk at the spectacular spirit manifestations was a woman who caught Olcott’s eye. She stood out not merely for the bright red shirt she wore in the style of revolutionary nationalists in Italy but her striking and exotic features—a face which suggested, as he later recalled, “power, culture, and imperiousness.” Outside, after lunch, he saw her roll a cigarette and put it to her lips. He rushed over, struck a match, and said—having overheard her conversing in French with her female companion—“Permettez-moi, madame.”

Olcott was, among other things, a journalist. Years ago, at 26, he had gone undercover in antebellum Virginia, risking his life to report on the execution of militant abolitionist John Brown for an anti-slavery newspaper in New York. When the Civil War broke out, he enlisted in the Union Army and received a special commission that allowed him to apply his investigative skills and progressive outlook to the federal administration. For three years, he not only traveled tens of thousands of miles and interviewed thousands of witnesses to expose corruption in Army and Navy contracts but initiated better practices to guard against future abuses. So well respected was his work that he was appointed one of three lead investigators when Lincoln was assassinated. After the war, having established himself as a specialist in insurance law with a successful practice in New York City, he made comprehensive proposals to improve regulation of the industry, though these were not so readily accepted as his reforms in military accounting.

As interim drama editor for the New York Sun during the summer of 1872, he embarked on a further campaign of reform—this time of public morals. In a series of reviews, he denounced current productions for their suggestive dialogue, immodest costumes, and licentious themes. Not long afterward, he separated from his wife, who filed for divorce on the ground of adultery at a house of prostitution. As he admits in his memoirs, he was then “a man of clubs, drinking parties, mistresses, a man absorbed in all sorts of worldly public and private undertakings.”

And yet amid this activity something was missing, and one day in July 1874, at the age of 42, he decided to seek it out. “I was sitting in my law-office thinking over a heavy case in which I had been retained by the Corporation of the City of New York,” he writes, “when it occurred to me that for years I had paid no attention to the Spiritualist movement.” Stepping out to pick up a weekly journal devoted to the subject, he read reports of the curious apparitions in Chittenden and—considering that, if they were accurate, “this was the most important fact in modern physical science”—resolved to go and investigate on the spot.

The account of his first visit, printed in a popular New York daily, received international attention. Now, accompanied by a sketch artist, he had come back to carry out a more fine-grained inquiry for an illustrated evening paper. This time, having “made the necessary disposition of office arrangements,” he planned a longer stay, and for a month now his reports had been published twice weekly. These dispatches had so far attracted considerable interest, including on the part of the individual he had just approached, who turned out to be a Russian lady of distinguished birth by the name of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky.

“I hesitated before coming here,” she told him, “because I was afraid of meeting that Col. Olcott.”

“Why should you be afraid of meeting him?” he asked.

“Oh! because I fear he might write about me in his paper.”

It seems never to have occurred to Olcott that Madame Blavatsky had come there especially with that aim. But even she could not have anticipated how easily he fell under her spell. What drew him to her was not physical desire. In fact, as he writes, “her every look, word, and action proclaimed her sexlessness”; before the visit was over, he was calling her Jack, and she signed her first letters to him with that name. What attracted him, rather, was her charm, her chain-smoking bohemianism, her singular presence in that drab American setting, her worldliness as a French-speaking Slavic aristocrat who had spent the past quarter century crisscrossing the globe.

She, for her part, soon came to understand what he was seeking—not just a story but a new cause to which to dedicate his life. And that is exactly what she, at length, supplied.

Moloney and Mulligan

But first she gave him the story he had come for. That night in place of the usual collection of departed spirits to which Olcott’s readership had hitherto become accustomed—all Americans and Red Indians, apart from two little German children—there appeared to the assembled guests a Russian peasant girl, a servant boy from the Caucasus, and a Muslim merchant from Tiflis. Another evening they were visited by “a Koordish cavalier armed with scimitar, pistols, and lance; a hideously ugly and devilish-looking negro sorcerer from Africa; and a European gentleman wearing the cross and collar of St. Anne, who was recognised by Madame Blavatsky as her uncle.” The evident impossibility of these strange manifestations having been fraudulently contrived by the poor, illiterate, native-born owners of the farm seemed impressive proof of their reality. At the same time, their mysterious association with Madame Blavatsky allowed her to steal the spotlight. She was, Olcott and his readers were given to understand, no ordinary medium: “instead of being controlled by spirits to do their will,” he wrote, “it is she who seems to control them to do her bidding”—a circumstance he might have reflected on more deeply.

After spending a fortnight with Blavatsky in Chittenden, Olcott returned to New York in her company and over the course of the following year grew ever more deeply involved with her, both spiritually and materially. In August 1875, she was installed at his expense in an apartment near his club, where he visited her daily, and by the end of November she and he were occupying the first and second floors, respectively, of an address on West 34th Street. Six months later, they moved again to share a large suite of rooms at 48th Street and Eighth Avenue, which was soon dubbed by the press the “Lamasery” for its exotic furnishings (Japanese cabinets filled with Oriental curios and a stuffed ape with a lecture on natural selection tucked under its arm) and reputation as a meeting place for the mystically inclined. In the evenings, sitting side by side at a big table, they would work on articles, books, and letters, after which, “in our playtimes,” as Olcott recalled,

she would tell me tales of magic, mystery, and adventure, and in return get me to whistle, or sing comic songs, or tell droll stories. One of the latter became, by two years’ increment added on to the original, a sort of mock Odyssey of the Moloney family, whose innumerable descents into matter, returns to the state of cosmic force, intermarriages, changes of creed, skin, and capabilities made up an extravaganza of which HPB seemed never to have enough.

Blavatsky at last took to calling Olcott Moloney, and he in fond retaliation would address her as Mulligan.

They were intimate friends—“chums,” as Olcott puts it in his memoir. The relationship fulfilled his taste for cosmopolitan glamor, his need for intellectual companionship, and above all his longing for a cause. He was, in fact, recruited to a whole series of causes, with a new one arising the moment interest in its predecessor started to fade. First came the defense of Spiritualism against the ignorant prejudices of modern science. Then the reform of Spiritualism—ridding it of fraud and links to radical social movements—on the basis of an ancient wisdom revealed by Blavatsky’s hidden occult teachers, the Masters. And then the exposition of this ancient wisdom and its defense against not just modern science but now also Spiritualism.

Olcott being of an empirical turn of mind, in order to motivate these successive campaigns resort was made to the production of phenomena that could be seen or heard. Upon their return from Vermont, Blavatsky’s contact with spirits continued for a time, albeit in more conventional forms such as rapping, tipping tables, and spelling out messages. The subsequent turn away from Spiritualism was announced by a more extraordinary communication: a strange letter on green stationery that arrived in a black-glazed envelope addressed in gold ink to Olcott. The letter was signed by Tuitit Bey of the Egypt-based Brotherhood of Luxor, one of Blavatsky’s Masters, who urged his new student: “Rest thy mind—banish all foul doubt. Sister Helen is a valiant, trustworthy servant. Have faith and she will guide thee to the Golden Gate of truth.” From then on, letters from various Masters came regularly, sometimes by mail but more often simply materializing on desktops or dropping down mysteriously from overhead. Most concerned themselves chiefly with Blavatsky and her troubles (which she must be protected from), her needs (which must be provided for), her plans (which must be furthered), and her shortcomings (which must be excused).

In November 1875, the Theosophical Society was founded with Olcott as president and Blavatsky corresponding secretary. That Olcott should outrank his companion despite her preeminence in spiritual matters reflects a basic division of labor between the two. Blavatsky, a creature of the salon, was out of place at the lectern; Olcott shined as a public speaker and organizer but lacked Blavatsky’s charismatic gift. As Annie Besant, Olcott’s successor as president of the society, observed in 1932, “H.P.B. gave to the world Theosophy, H.S. Olcott gave to the world the Theosophical Society.”

The Society’s aim was to strike out where materialistic modern science dared not go and rediscover the true, spiritual science of the esoteric sages of the past. In his inaugural address, Olcott portrayed the group’s 34 members as the advance-guard of a great reform like abolition, that “holy cause”—as its partisans famously called it—of his youth: “I feel that we are enlisted in a holy cause, and that truth, now as always, is mighty and will prevail.” Over the course of the next twelve months, the Society’s numbers rose apace, adding over a hundred new members, and no less abruptly dwindled until, by the end of 1876, the organization was, in Olcott’s words, “comparatively inactive: its By-laws became a dead letter, its meetings almost ceased.”

At this point, perhaps out of desperation, Blavatsky introduced Olcott to yet another cause: the promotion of Eastern religion, now seen as closely akin to the ancient wisdom previously taught, and its defense against Christianity and colonial suppression. A corollary of this turn to the East was a new plan for the two of them to settle for a time in that adopted homeland, join forces with their Hindu and Buddhist brethren there, and learn from them with a goal of one day returning to spread their doctrines—in a suitably “esoteric” and non-sectarian form—to the West.

Though Olcott soon came to share Blavatsky’s “insatiable longing to come to the land of the Rishis and the Buddhas, the Sacred Land among lands,” he was no footloose aristocrat like her but a professional man with responsibilities who, as he put it, “could not see my way clear to breaking the ties of circumstance which bound me to America.” Apart from his law practice, these attachments included his ex-wife, to whom he owed alimony and child support, and his two sons, then 15 and 16. The new direction thus called for a phenomenal inducement more dramatic than a mere written message, however outlandish its appearance or mode of delivery.

And so one evening as Olcott sat reading before bed with quiet absorption, a flash of white appeared in the corner of his eye. He turned and dropped the book. Before him stood the towering figure of a man from the East. He was dressed in white, with long black hair, a long black beard parted at the chin “in Rajput fashion,” and a finely embroidered turban on his head. Olcott instantly knew himself to be in the presence of one of his Masters, who were lately also called “Mahatmas,” having—as Blavatsky’s spiritual authority drifted eastward—by insensible degrees adopted vaguely South Asian names and relocated from their Egyptian seat to a remote Himalayan valley. And now here was one in the flesh, or at least the paranormal semblance of such. The latter sat down before Olcott and, fixing him with his penetrating eyes—those of “a mentor and a judge, but softened by the love of a father”—informed him his life had reached a critical point. A great task for the good of humanity lay before him, should he choose to take it up. He went on to speak in intimate detail of Sister Helen, to whom Olcott was bound by a “mysterious tie… which could not be broken, however strained it might be at times.”

When this strange apparition at last rose to go, the practical-minded Olcott suddenly wondered how he could ever prove to himself and others he was neither hypnotized nor dreaming. Then, just before disappearing, the figure, as though in answer to this unspoken question, unwrapped his turban and laid it on the table—a cherished souvenir of the visitation, which Olcott would count as “chief among the causes of my abandonment of the world and my coming out to my Indian home.” In fact, as he recalled, “before the dawn of that sleepless night came, I began to devise the means and to bend all things to that end.”

The White Buddhist

On December 17, 1878, Olcott and Blavatsky went ashore in Bombay. Their arrival was reported in the Allahabad Pioneer, which noted that while Western visitors to India had hitherto “come to govern, to make money, or to convert the people to Christianity,” the Theosophists had another motive: a “loving enthusiasm for Indian religious philosophy.” They were making pilgrimage to sacred soil, as Olcott immediately made clear: “The first thing I did on touching land,” as he recalled, “was to stoop down and kiss the granite step, an instinctive act of pooja!”—that is, of worship. He and Blavatsky went on to show their disregard for the colonial color line by not only settling in the city’s native section but sharing meals and sleeping quarters with its residents on terms of equality. Olcott soon went so far as to adopt Indian dress, trading his suit and shoes for a kurta and chappals.

Before his arrival, Olcott had entered into a lively exchange of letters with leaders of native faiths across South Asia. Among his most notable correspondents were several pioneers of the Buddhist revival in Ceylon, as Sri Lanka was then known. The movement had arisen some ten years earlier as a nascent Sinhalese national resistance against colonial rule, which in this early stage expressed itself as a protest against the spread of foreign customs. The island had been a possession first of the Portuguese, then of the Dutch, and finally of the British, who had imposed Christianity and the English language upon the new administrative classes through control of education and the civil service while giving missionaries free rein among the rest of the population. At the head of the revival were educated monks who, though effective in their arguments and personally revered, were geographically scattered and divided by lines of region, sect, and caste. Yet all welcomed Olcott’s support and urged him to visit.

In May 1880, Olcott and Blavatsky sailed to the island, where they were greeted by the waving of a thousand flags and cries of “Sadhu! Sadhu!” (“Peace be unto you!”). The reception was no mere show. Olcott’s letters on religious questions, which had been circulated by his Ceylonese contacts, had aroused great interest, and the arrival of these sympathetic foreigners had been widely anticipated. For the duration of their visit, the adoring crowds never dissipated and grew thicker still once the honored guests, in a formal ceremony held shortly after their arrival, “took pansil”—that is, made public vows in the ritual language of Pali to adhere to the tenets of the Buddha, as no Westerner had ever done. Word that a white man and a “Russian princess” had turned their backs on Christianity to embrace the native religion spread far and wide.

As they toured the country over the next two months, they “passed from triumph to triumph,” as Olcott recalled. “The people could not do enough for us, nothing seemed to them good enough for us: we were the first white champions of their religion, speaking of its excellence and its blessed comfort from the platform, in the face of the Missionaries, its enemies and slanderers.” When they visited the former royal complex in Kandy, not only were they welcomed by the chief priests of its temples and monks of the highest rank but granted the special privilege of being shown the island’s most sacred relic: a tooth of the Buddha, which Olcott describes as being the size of an alligator’s and “much discolored by age.” When they returned to their lodgings, Blavatsky was asked by some educated Sinhalese gentlemen her opinion of the relic’s authenticity. Her reply was diplomatic: “Of course it’s his tooth: one he had when he was born as a tiger!”

Olcott had come to South Asia a humble student of its spiritual traditions, but soon after his arrival in Ceylon he rather incongruously assumed the role of teacher. He had been there only two weeks before delivering a lecture written on the spot on the subject of “Theosophy and Buddhism,” and he followed it a week later with another on “The Life of the Buddha and Its Lessons.” Throughout the trip, he spoke to crowds of two, three, four, and five thousand people who received his words in reverent silence. He met, moreover, with leading clerics and lay activists across the island, including representatives of all three monastic sects, and began taking the initiative to overcome the divisions that had previously thwarted their organization on a national level. Toward the end of the visit, he succeeded in arranging a conference between the two largest sects, whose priests were so socially distant they refused to eat in the same room, and persuaded them to appoint delegates to a body representing the interests of the Buddhist community as a whole. “This was quite a new departure,” Olcott explains, “joint action having never before been taken in an administrative affair; nor would it have been now possible, but for our being foreigners who were tied to neither party, nor concerned in one of their social cliques more than in any other.” Against all expectation, he found himself the sole universally recognized leader and moving spirit of a popular campaign of national self-assertion.

While Blavatsky was respected and acclaimed in Ceylon, here Olcott for the first time emerged from her shadow. She was no public speaker, had little organizational gift or interest, and as a woman enjoyed less freedom or authority in dealing with traditional religious figures. It was left to Olcott to take the chief part in discussions with these men and in setting up across the country new branches of the Theosophical Society. Of these, only one, composed of free thinkers and occult students, was aligned in its concerns with other branches around the world. The other eight, designated branches of the “Buddhist Theosophical Society,” were in fact nothing but communal organizations of the Sinhalese religious majority with an objective of promoting their ancestral faith, including by founding affiliated schools for boys and girls as an alternative to missionary and government schools.

As Olcott had come to realize, the religious education of youth was the key to the Sinhalese Buddhist revival. Of the existing 1,200 government-sponsored schools, only two, with a total attendance of 246, offered instruction in Buddhist teachings. The rest either taught only secular subjects or, like the 805 missionary schools, engaged in Christian indoctrination. As a result, Olcott observed, “the entire nation was virtually ignorant of the basic principles of their religion, or even one of its excellent features.” On his return to India, he devised a scheme to collect money for a National Education Fund that would vastly extend the educational mission of the Buddhist Theosophical Societies and planned to go back on his own for a much longer tour of the country to organize the effort.

In forming these intentions, Olcott naturally consulted Blavatsky and the Masters. He was gratified to receive their full approval and accordingly wrote his hosts in Ceylon to make arrangements for the trip, which they eagerly awaited. Then, two months before he was to leave, Blavatsky insisted he cancel his plans to help her edit The Theosophist, their monthly journal. He refused, and she lost her temper. She locked herself in her room for a week and, communicating only in writing, warned him the Masters had withdrawn their support for the undertaking in Ceylon. If he persisted in it, they would wash their hands of him and the whole Society. Olcott responded, as he later wrote, “that I did not believe them to be such vacillating and whimsical creatures; if they were, I preferred to work on without them.” He had seldom before defied Blavatsky’s wishes and never the orders of the Masters, but until now the occult teachers of his daydreams had always encouraged his projects for social change. Now that he was forced to choose between the spirit of reform and obedience to an esoteric hierarchy, his course of action was clear. After a few days, he received a note signed by Master Koot Hoomi Lal Singh: “Let her alone and do not go near her for a few days. The storm will subside.”

Olcott returned to Ceylon in April 1881. Though the crowds that flocked to see him were much diminished—the popular enthusiasm raised by his first appearance with Blavatsky having worn off—it is for the work done on this second tour that Olcott is remembered in Sri Lanka to this day.

On his arrival, he gathered the principal leaders of the two main sects in Colombo to agree on the fund’s basic principles and outline a plan for the collection drive, which they promised to support. But there remained the question of what it was that schools for the religious education of Buddhist children ought to teach. No modern presentation of the tradition’s elementary precepts existed, and when Olcott’s call to produce one went unheeded he resolved to do it himself. Since his first visit he had read more than 10,000 pages of scriptures and commentaries in French and English translation, and days before arriving in Colombo he completed the first draft of a handbook in question-and-answer form. Once it had been translated into Sinhalese, he met with the high priest of the southern region, Hikkaduwe Sumangala, and spent long days with him going over the text word by word before the latter would approve its use. The Buddhist Catechism, published in English and Sinhalese that July, would in Olcott’s lifetime go through 40 editions in 20 different languages and is still read today. Despite its certification of orthodoxy, the work has been criticized in academic studies for setting forth what amounts to a liberal Protestant version of Buddhism that grounds itself on the “pristine purity” of the earliest doctrines as preserved in sacred texts in preference to the “pagan, mean, spurious” folk practices of popular religion. But such a tendency was not in conflict with that of the native reformers with whom Olcott was working, and the book’s wide acceptance speaks for itself.

Over the course of the next six months, by rail, by boat, on elephant back, and in a custom-made bullock cart of his own design, Olcott visited the inhabitants of the Western Province of the island village by village, “rousing popular interest in the education of their children under the auspices of their own religion, circulating literature and raising funds for the prosecution of the work.” The sums he managed to collect were disappointing, but they added up to enough to establish sixty schools offering an English-language education in both secular and religious subjects. By the early 1960s, their numbers had grown to 400, and, though now under government control, they remain in use today.

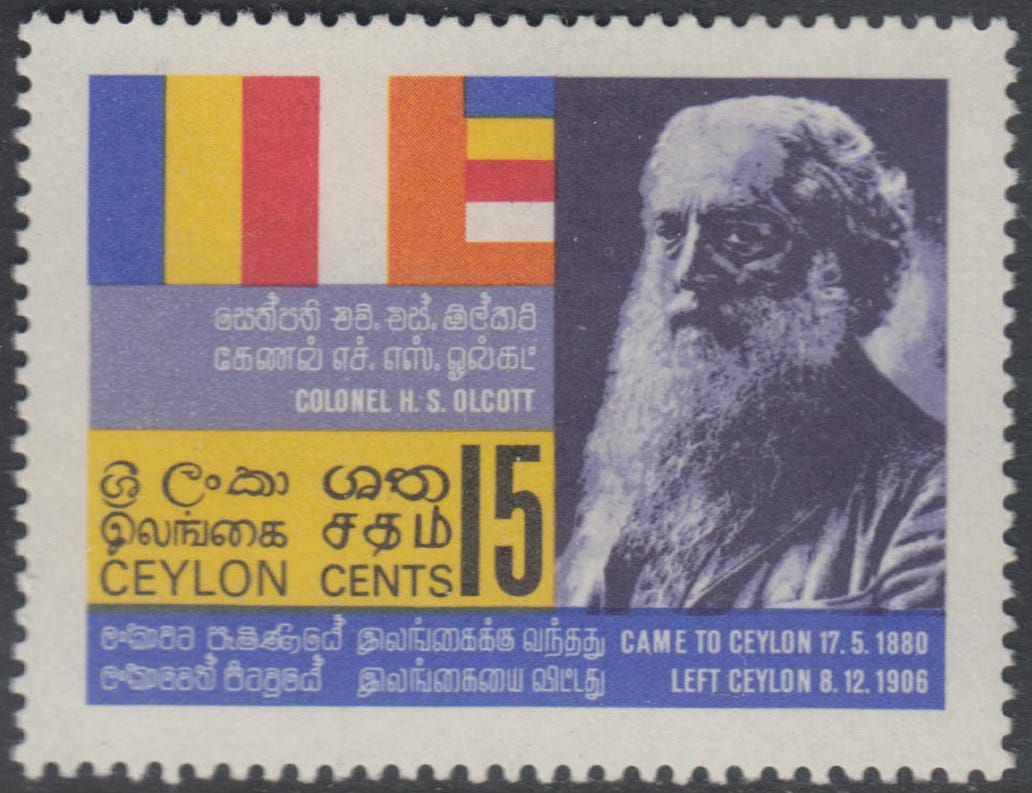

Olcott was pleased with all he had accomplished on this and one subsequent tour of the country, and only regretted he had not thought of the project on the occasion of his first visit, when he might have raised ten or twenty times as much, or indeed had not “devoted my whole time and energies to the Buddhist cause from my early manhood,” as had he done so he was sure to have brought about a complete reconciliation between the three rival sects and “planted a schoolhouse at every cross-road in this lovely land of the palm and the spice grove.” As it is, the “White Buddhist,” as he is known, is honored in statues and on postage stamps in Sri Lanka today. The date of his death is commemorated every year, and on the sixtieth anniversary in 1967 the prime minister proclaimed him “one of the heroes in the struggle for our independence and a pioneer of the present religious, national and cultural revival.”

When his second tour was over, Olcott returned home to India, where, thanks to his organizing talent and the capability of his native assistants, he found everything in order at Theosophical Society headquarters. And yet, as he recalled, “a rude shock awaited me.” Blavatsky relayed to him the Masters’ warm congratulations on his success in Ceylon—quite as though they had never forbidden him to go there or threatened, if he did, to have nothing more to do with him or the Society.

The incident marked a turning point in his relationship with his companion and guide. “Thenceforward, I did not love or prize her less as a friend and a teacher,” he writes, “but the idea of her infallibility, if I had ever entertained it even approximately, was gone for ever.”

Sources

I consulted Henry S. Olcott, People from the Other World (1875); A Collection of Lectures on Theosophy and Archaic Religions Delivered in India and Ceylon (1883); and Old Diary Leaves, First and Second Series (1895). A resource from NYU Libraries collects Olcott’s undercover reports of John Brown’s execution for the New York Tribune.

On Olcott’s life and career and the history of the Theosophical Society, see Gertrude Marvin Williams, Priestess of the Occult: Madame Blavatsky (1946); John Symonds, Madame Blavatsky (1959); Bruce F. Campbell, Ancient Wisdom Revived (1980); Marion Meade, Madame Blavatsky: The Woman Behind the Myth (1980); Michael Gomes, The Dawning of the Theosophical Movement (1987); Peter Washington, Madame Blavatsky’s Baboon (1993); and Stephen Prothero, The White Buddhist: The Asian Odyssey of Henry Steel Olcott (1996).

On Olcott’s work in Ceylon, see the study by Stephen Prothero cited above and his “Henry Steel Olcott and ‘Protestant Buddhism,’’ Journal of the American Academy of Religion (1995), as well as L.A. Wickremeratne, “Religion, Nationalism, and Social Change in Ceylon: 1865-1885,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1969).

That was an absolutely brilliant opening sentence! Perfect. And I really enjoyed the rest of the post, too.

Great stuff again, Alan!