In 1902, William Wynn Westcott, London coroner and Supreme Grand Secretary of the Rite of Swedenborg—among other strange and eminent titles—was trying to bring the society in question, which some twenty years earlier had fallen inactive, back to life. Having managed to recruit the author and fellow occultist A.E. Waite, he sent him a manuscript of the group’s ritual to copy by hand and return, apologizing for its “prohibitive length”—over 200 pages. Waite recorded the loan in his diary and added of Westcott: “He is a man whom you may ask by chance concerning some almost nameless rite and it proves very shortly that he is either its British custodian or the holder of some high if inoperative office therein.”

The flowering of fanciful orders and rites at the fringes of British freemasonry was a minor cultural phenomenon of the latter part of the Victorian era, and Westcott had by 1902 been part of the scene for a quarter of a century. He arrived a bit late, after the initial burst of activity had spent its force.

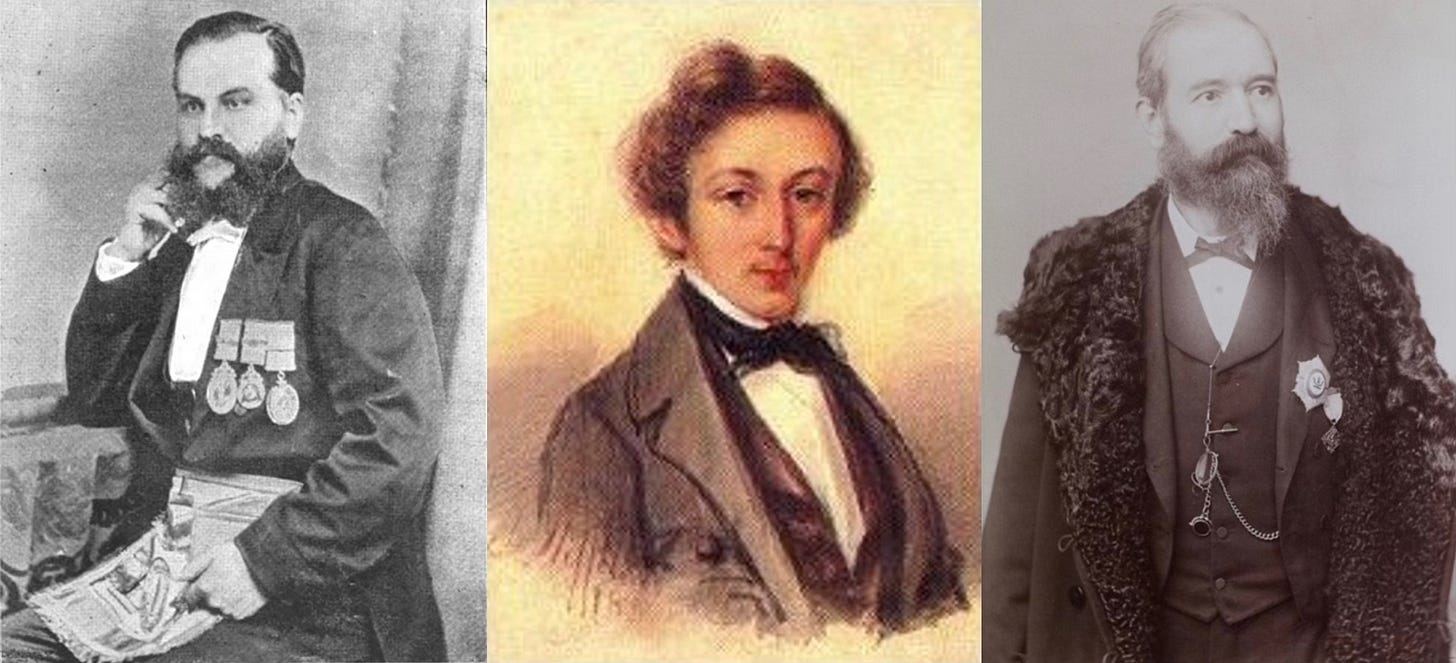

The most successful of these groups had been the first: the Imperial, Ecclesiastical and Military Order of the Knights of the Red Cross of Rome and Constantine, which claimed to be a medieval religious order with roots in a chivalric order of late antiquity. The society was founded—or rather “revived”—in 1865 by twenty-five-year-old Robert Wentworth Little, a clerk and cashier in the office of the Grand Secretary at Freemason’s Hall in London. By 1871, it would have some 50 conclaves in England and a dozen more overseas. None of its successors—including three more groups started by Little: the Rosicrucian Society of England, the Ancient and Primitive Rite of Misraim, and the Ancient and Archaeological Order of Druids—ever came close to matching its popularity, in part because their Eastern or esoteric motifs lacked the broad appeal of the Red Cross Knights’ theme of Christian chivalry.

By the time Westcott got involved in 1877, Little was in poor health, already afflicted with the tuberculosis that would soon kill him at the age of 39, and the trend he had set in motion was petering out. Westcott’s belated start would hinder his advancement and cause him a good deal of trouble, but in the end he would improbably succeed—if only for a time—in realizing the movement’s fondest dreams.

My story begins in 1871, when Westcott left school in London and returned to the rural county of Somerset to inherit an elderly half-uncle’s medical practice. There he started his career in conventional masonry, joining two craft lodges and a Royal Arch lodge. He even enlisted in a local conclave of Little’s Knights of the Red Cross of Rome and Constantine.

Before long, he met Captain Francis George Irwin, a middle-aged army officer retired to Bristol, where he directed a volunteer unit. Irwin was a Spiritualist, an occult student, and a devoted freemason whose craving for the so-called higher grades was often remarked upon. “So great was his desire to obtain more light,” said one who knew him, “that there was scarcely a degree in existence, if within his range, that he did not become a member of.” At Irwin’s prompting, Westcott followed him into two widely accepted side degrees: Mark Masonry and the Scottish Rite.

Having, as another contemporary noted, not only “a passion for Rites” but “an ambition to add to their number,” Irwin chartered from Canada the aforementioned Rite of Swedenborg, which was supposed to be a revival of an eighteenth-century system based on the teaching of the Swedish visionary. “Tis a beautiful degree elucidating the craft degrees in a marvellous manner,” Irwin boasted to Westcott in a letter inviting him to join. “My Ritual extends over 212 pages of closely written sermon paper.” Westcott was among the first admitted, and when the Rite’s Supreme Grand Lodge and Temple of Great Britain and Ireland was opened in Manchester with 11 members, he was named Supreme Senior Grand Dean—his first “grand office” at the age of 28.

Among the other officers were three men we will meet again: Kenneth Mackenzie, a polymath who had betrayed his early promise and now scraped together a living by occasional journalism and the use of an astrological system to bet on horses; John Yarker, an import-export merchant whose voyages to distant seaports allowed him to collect such unusual honors as the Constantinian Order of St. George and the Star of Merit of the Rajah of Calcutte; and Benjamin Cox, an accounts clerk for a local town council who sycophantically assisted Irwin in his masonic and quasi-masonic pursuits.

The order’s lengthy ritual of which Irwin was so proud had its drawbacks. Never printed for reasons of secrecy, it was burdensome to transcribe by hand, and so copies were scarce. “Where can I get hold of a Ritual of Sweden,” Westcott wrote Cox in advance of a meeting where he was to initiate an important recruit. “Irwin had lent his when I asked him.” The shortage of materials and regalia was surely one reason why, despite some early growth, the society promptly lapsed into quiescence.

Westcott must soon have suspected all was not well in the shadowy world into which he had been introduced. A month and a half after being invited to join the Swedenborg Rite, he wrote to Irwin with a studied nonchalance, “Will you let me know, where is a meeting of the Rosicrucian Soc. in this country, no hurry.” He meant the Rosicrucian Society of England, a small masonic study group founded by Little that took inspiration from a mythical esoteric fellowship of the fifteenth century. Irwin, who headed the society’s Bristol branch, neglected to reply to Westcott’s query. The fact was there had been no gathering in Bristol since April 1873, and due to a decline in membership the branch would never meet again.

The following year, Westcott applied to join the Royal Oriental Order of Sikha (Apex) and the Sat B’hai, a supposed Hindu rite said to be imported by an Indian army captain, J.H. Lawrence Archer. Irwin had secured a charter, Mackenzie was busy working up an elaborate ritual based on a purported Sanskrit original in Archer’s possession, and Yarker was handling the order’s correspondence. After hearing nothing about the status of his candidacy for some time, Westcott wrote to Irwin, again affecting a world-weary tone:

The Rite of Apex received my fee & I have never had anything from it, but 2 little pamphlets. I have seen in The Freemason that there have been meetings, but I have never been informed of them: so that I feel rather inclined to resign any share in the very dead alive Order.

He must have received a rather sharp response because he wrote back four days later to apologize for any impression he may have given of raising an accusation against Irwin himself.

However impertinent it might have been to address his observation to an Arch Censor of the order, Westcott was not wrong in thinking something funny was going on. Like many promising new groups of recent years, the Sat B’hai had simply fizzled out. Archer seems to have realized there was no real money to be made from these men and grown evasive. Irwin was making noises about quitting and Yarker was no longer heard from at all, leaving Mackenzie—with his unfinished ritual—the last true believer until in another year’s time even he gave up. Meanwhile, another society of allegedly Eastern origin that Mackenzie, with the support of Irwin and Cox, was struggling to organize—the Ancient Order of Ishmael—would also come to nothing.

After 1878, those in London wishing to learn the higher mysteries of the East could simply join the popular Theosophical Society. Led by a woman, it was open to all. With one partial exception, the orders founded by Irwin, Yarker, and Mackenzie admitted only freemasons—a policy which no doubt limited their growth. One group Westcott did manage to join—Irwin and Yarker’s Royal Order of Knights of Eri and Red Branch Knights of Ulster (said to have been founded in Ireland in 90 BC!)—went so far as to restrict its enrollment to advanced members of another small group of esoterically minded master masons, namely the Rosicrucian Society. When Westcott was let in in 1880, he was the first addition to the original nine members in its eight (or is that 1,961?) years of existence.

And yet the obstacles faced by Westcott were not merely organizational but generational. Irwin, Yarker, Mackenzie, and Cox were all older than him by 15 or 20 years; when he met them in his mid-twenties, they were all in their forties. As a younger novice, he often found himself barred from the innermost sanctuary.

For instance, he was not admitted to the Fratres Lucis, a secret group founded by Irwin in the mid-1870s in which Westcott surely would have taken the keenest interest. Its objects of study were “natural magic, Mesmerism, the science of death and of life, immortality, the cabala, alchemy, necromancy, astrology, and magic in all its branches.” So select was the membership, which was said to include the noted Spiritualist Frederick Hockley, that Mackenzie and Cox—Irwin’s closest associates—had to beg to be admitted. Westcott must have been sorely disappointed not to make the cut.

Nor did matters soon improve. In 1886, after Mackenzie had died, Westcott was still brooding over his failure to join the Sat B’hai. Having spoken to Mackenzie’s widow, he wrote to Irwin:

Mrs. Mackenzie tells me there is a fine Ritual, but I have never seen it…. Mrs. Mackenzie also in an oracular manner, said she knew why I had been passed over, but decline[d] to tell. Can you solve the Mystery?, when you have leisure.

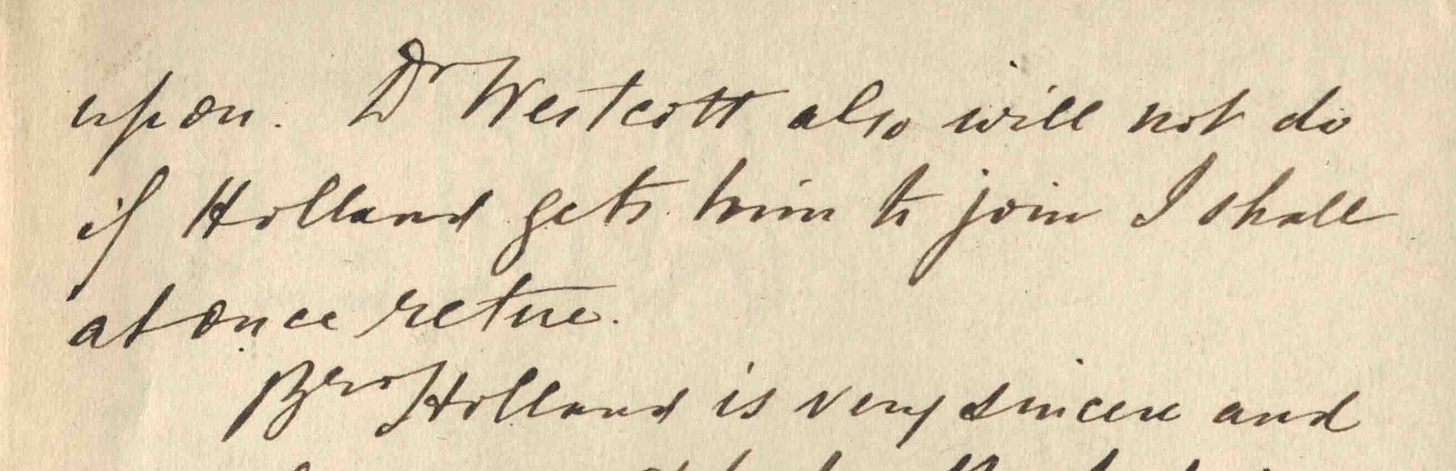

He was right to suspect some intrigue, as we know from a letter to Irwin in Mackenzie’s hand dated August 24, 1883. Mackenzie was then helping the chemist and metallurgist Frederick Holland to set up the Society of Eight, a rather exclusive group—as its name suggests—devoted to the study of alchemy. Besides Holland and Mackenzie, three members had so far been invited: Irwin himself, Yarker (of course), and the Rev. W.A. Ayton, an elderly clergyman who would one day join the Golden Dawn. In the letter, Mackenzie discusses a few candidates for the three remaining spots and insists: “Dr. Westcott also will not do[. I]f Holland gets him to join I shall at once retire.”

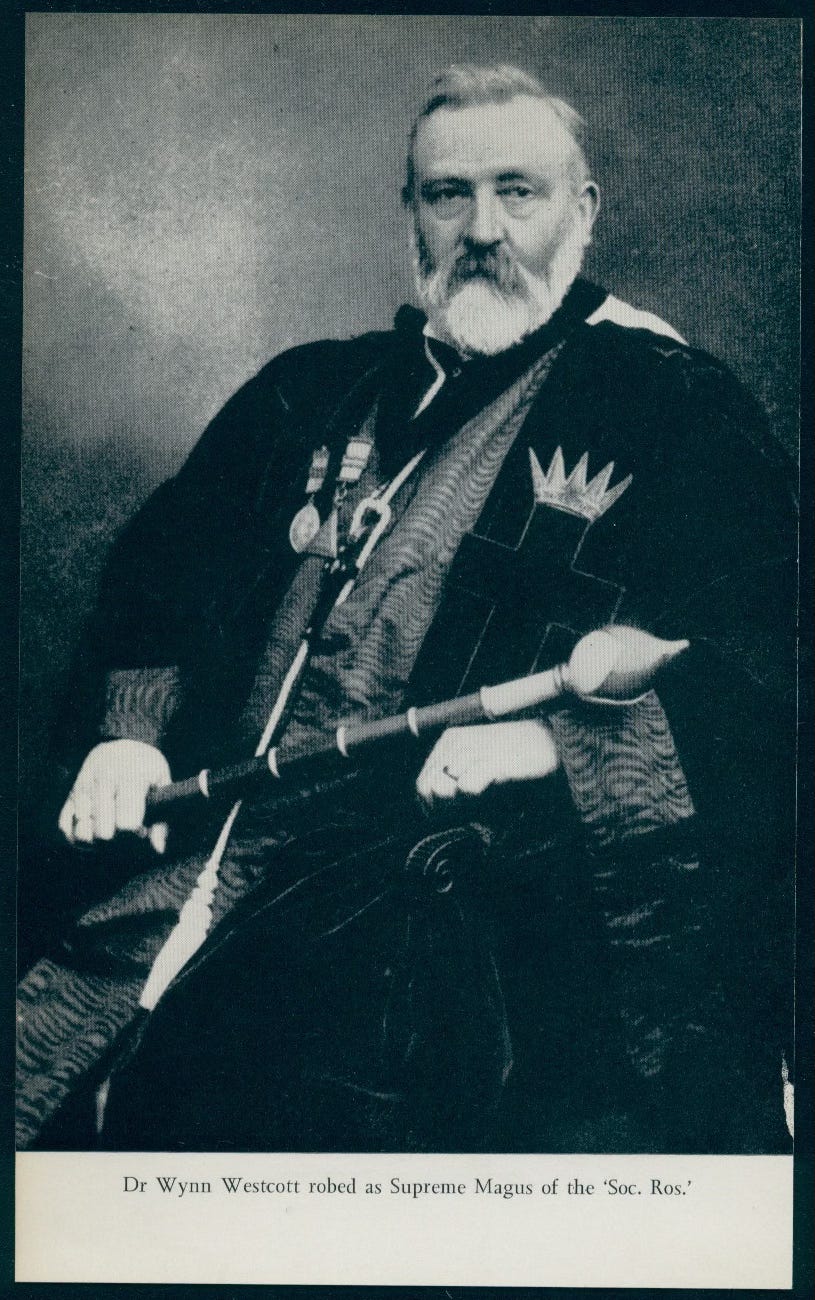

By 1880, Westcott had moved to the London suburb of Hendon, and that April—little thanks to Irwin—he managed to join the metropolitan branch of the Rosicrucian Society. Mackenzie, once the society’s Assistant Secretary-General, had quit in a pique some years earlier, and Little, its founder, had recently died. A new leadership was in place, and Wescott must have found it congenial. He was to remain an active member for the 45 years left to him, ruling for the last 34 as its Supreme Magus.

But he did not forget his first grand office and the order that had initiated him into the joys of esoteric ritual. In 1885, in an effort to restore interest in the Rite of Swedenborg, he placed a letter about the society in Yarker’s journal The Kneph. “For some unknown cause,” he observed in disbelief, “the Lodges do not now carry on the working.”

The following year, he wrote Yarker with news that Mackenzie was gravely ill: “I fear he cannot live much longer.” His concern was not unmixed with the hope that the death of the Supreme Grand Secretary of the Swedenborg Rite would allow him to succeed Mackenzie in the office and, with Yarker’s help, revive the order. Westcott would first need to get hold of the “documents, ritual etc.” from Mackenzie’s widow, which might be a tricky proposition. “If you will send me a warrant, as from you as Grand Master, to obtain them,” he urged Yarker, “I will act after his funeral.”

Mackenzie died on July 3, 1866. He was only 52 years old, and his marriage of 13 years had been a happy one. Westcott nonetheless lost no time in writing to Alexandrina Aydon Mackenzie, his sense of mission supplanting any feeling for the latter’s loss. So impatient was he that when he did not receive an immediate reply he had Irwin write on his behalf only three weeks after the sad event.

On August 4, he finally heard from the bereaved, who offered to let him come “at 24 hours notice” and collect the “Swedenborgian things” she had been able to locate among the documents her late husband had amassed, which was not easy: “I have thousands of papers, and books and they are so mixed.” Westcott took away bundles of certificates, seals, printed constitutions, a membership list, “and some loose papers.”

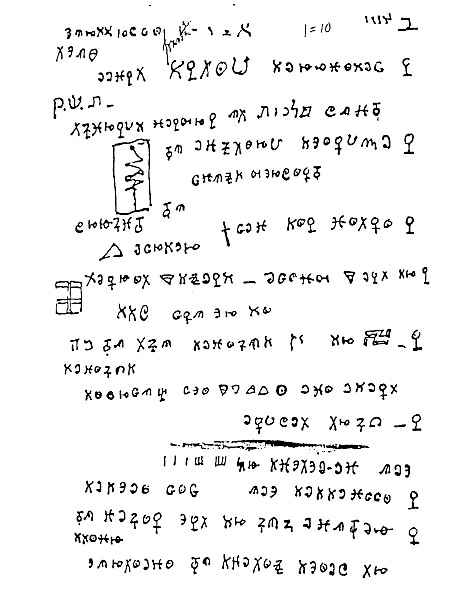

He did his best to recruit members to make use of these materials, and as we have seen he was still trying as late as 1902. He and Yarker also made an effort to breathe life into Mackenzie’s stillborn Order of Ishmael, whose basic documents must have been among the “loose papers” picked up by Westcott. But it was another such manuscript, inscribed on sixty folios in an old alchemical cipher, whose discovery marked a turning point in his career as a propagator of strange rites and a minor landmark in the cultural history of the West.

He identified the cipher, which was taken from a seventeenth-century cryptographic work well known in his rarefied circles, and began to decode the document, scrawling on the backs of printed summonses to past meetings of the Swedenborg Rite. As he did, the outlines of a series of rituals for the use of an unnamed initiatory society was revealed to his eyes. They indicated the group to which they belonged had two features not often seen in those dreamed up by Mackenzie’s network and until now never combined in one.

For one thing, they were based on Western hermetic traditions, including alchemy, astrology, Rosicrucianism, the Kabbalah, the doctrine of the four elements, the Enochian magic of John Dee, and the occult significance of the Tarot pack, a notion which Mackenzie was the first to spread in England. And for another, the rituals spoke of members of the order as fratres and sorores—brothers and sisters. The inclusion of women made clear this was no masonic society.

Westcott did not tell Yarker or Irwin of his find. Instead, taking another pair of high-ranking Rosicrucian Society brothers as co-chiefs, he organized a secret society of his own—the Order of the Golden Dawn—with a rite worked up from the manuscript he had found among Mackenzie’s papers. Its source he shrouded, as was customary, in an origin myth designed to bear out the authority of the founders of the new society and the authenticity of its rituals and teachings.

According to this tale, the order is a very old and secret one, being an offshoot of the medieval Rosicrucian Brotherhood, itself the repository of a hidden tradition that goes back to antiquity. It had branches in England and France until modern times, when the deaths of several noted occultists of the previous generation—including Mackenzie—“caused a temporary dormant condition of Temple work.” A branch survives, however, on the Continent, and another has recently been revived in England after a set of “ancient M.S.S…. written in cypher” was stumbled upon at a London bookstall by a late masonic historian, the Rev. A.F.A. Woodford. Shortly before his death, the story goes, Woodford sent the manuscripts to Westcott with a tip to contact for more information a German lady whose address was found in a note among their leaves. She turned out to be a senior member of the order’s Continental branch. In a brief exchange of letters, Westcott and his co-founders were granted permission to carry out their work, at which point the correspondence was broken off by her death. In legend as in life, an older cohort had bequeathed an unexpected legacy and conveniently disappeared from the scene.

In March 1888, the Golden Dawn’s London temple was founded. Being open to non-freemasons, it attracted a still-younger generation of professionals and artists—W.B. Yeats among them—who were influenced by the fashionable mysticism of the 1890s. They included many talented women who would assume positions of leadership. As a secret and exclusive order of practicing occultists, the Golden Dawn neither achieved nor aspired to the relatively broad popularity of Little’s Knights of the Red Cross or the Theosophical Society. But over the next 12 years, almost 400 members joined the order’s five temples in England, Scotland, and France. The most advanced of these brothers and sisters were highly active, making daily use of the London temple for ceremonies, instruction, individual workings, and informal gatherings.

The Golden Dawn has been described as “by far the most successful occult society ever created.” It was the last, best invention of what Waite called Mackenzie’s “manufactory, mint or studio of Degrees,” plucked posthumously from his desk and given life by a younger man he disliked. Irwin, who died in 1893, declined to join for reasons of age, and Yarker was busy with his own concerns. But Cox enrolled in March 1888 and headed the small Osiris temple in Weston-super-Mare until his death seven years later.

The happy result of Westcott’s initiative kept him busy for nine years. In 1897, he resigned his office (though not his membership) for what were said to be professional reasons. Whatever the true cause of his stepping down, it was proof the society he created had taken on a life of its own.

Three years later, the project would blow up in his face. The gaps he spanned culturally (masonic vs. profane) and generationally (in 1900, Yarker was 67, Westcott 52, Yeats 35) had drawn to his new order a fresh breed of occultists who lacked any concept of a traditional history—that conventional desideratum of the masonic rite—and saw it as it a species of fraud. But that is a story for another day.

As for the Rite of Swedenborg, despite Westcott’s best efforts it never found a sizable following. Waite, for one, was unimpressed. In his Secret Tradition in Freemasonry (1911), he describes at some length its painfully protracted initiation rituals. As he tells it, at the final step of the ceremony to be admitted to the society’s third and culminating grade, “[t]he Candidate is pledged to keep secret the Ineffable name of God, and in this connection a certain communication is made to him—which comes to very little, as usual.”

Sources

My principal sources on the history of the Rite of Swedenborg, Westcott’s career in fringe masonry, and his founding of the Golden Dawn are four articles by R.A. Gilbert: “William Wynn Westcott and the Esoteric School of Masonic Research” (1987), “Chaos Out of Order: The Rise and Fall of the Swedenborg Rite” (1995); “Provenance Unknown: A Tentative Solution to the Riddle of the Cipher Manuscript of the Golden Dawn,” reprinted as the introduction to The Complete Golden Dawn Cipher Manuscript by Darcy Küntz (1996); and “Seeking that which was Lost: More Light on the Origin and Development of the Golden Dawn,” Yeats Annual 14 (2001).

Helpful in tracing Westcott’s masonic career is the page on “WILLIAM WYNN WESTCOTT – freemasonry, fringe masonry and SRIA 1871- 1925” in Sally Davis’s detailed biographical research page on the members of the Golden Dawn. I also consulted the biography attached to “Cabinet print of William Wynn Westcott” in the catalogue of the Museum of Freemasonry.

The classic account of British fringe masonry is Ellic Howe’s “Fringe Masonry in England 1870–85” (1972).

The Golden Dawn is called the most successful occult society in A History of the Occult Tarot: 1870-1970 by Ronald Decker and Michael Dummett (2002).

I consulted correspondence related to Westcott and fringe masonry held by the Museum of Freemasonry. A digital reproduction of the Letter of K R H Mackenzie to F G Irwin (28 August 1883) from which my essay takes its title is accessible from their catalogue, which is free to search online.

This was so interesting. I've vague recollections of Swedenborgism in Sheridan le Fanu, so it was fascinating to hear some of the background.

This is amazing research. The Museum of Freemasonry must be an interesting place to visit.