Let’s consider a letter written by Kenneth R.H. Mackenzie of Chiswick Square, London to fellow occultist Capt. F.G. Irwin of Bristol on June 16, 1875, or—as the message is alternatively dated—the “2nd day of Mesore 6919.” The latter, of course, is the equivalent date in the ancient Egyptian calendar calculated from the accession of the pharaoh Menes in 5040 B.C., adding an extra four years “for a mystical reason.” In his letter of the previous week, Mackenzie had claimed to be the first student of Egyptology to have properly worked out the conversion. But this is by the way.

In the letter at hand, Mackenzie refers to the recent death of French occult writer Eliphas Levi, whom he had visited in Paris at the age of 29. While regretting the loss of that great authority on esoteric matters, he holds out hope it is not beyond recovery. “I am sorry to hear Eliphaz Lévi has left us,” he writes, “but I presume he would not be difficult to find as he was so well known to those who preceded him and his contemporaries. I don’t know whether I can get at him through my wife, who is a medium, but I will try.” As Mackenzie appears to see it, Levi may prove easier to call on in the afterlife than he was in life. No longer does one need to cross the Channel.

This casual attitude toward conversing with the dead was a habitual one for Mackenzie and his circle. The previous November, he had closed a letter to Irwin—who believed he was in regular touch with the spirit of the eighteenth-century occultist and adventurer Count Cagliostro—by asking after the latter and seeking his views on current affairs: “I should like to know what your friend Cagliostro is doing and what he says to things as they are.”

Mackenzie was then compiling a work of reference, the misleadingly titled Royal Masonic Cyclopaedia (the Bonkers Pseudo-Masonic Cyclopaedia gives a better sense of its contents). In August, coming to the entry on Cagliostro, he thought to draw on a rather unorthodox source. As he explained to Irwin,

Now I am very anxious in the article I am writing concerning Joseph Balsamo [Cagliostro’s real name] ... If your spirit friend would condescend to take an interest in the matter, not as a publicly avowed spiritualistic matter, but simply by way of correction or hints it would be very valuable.

In the end, Mackenzie received the help requested. When he finished the entry, he sent Irwin a copy for his approval—and not only his. “Of course I cannot say that the Count himself is to see this,” he ventured, “but I much want him to do so.”

Spiritualism in its modern form had been introduced to Britain in the early 1850s, and by 1875 it was in fashion among all classes of society. Seekers hoped to exchange personal information with departed friends or relatives and take comfort in their survival on another plane, or perhaps to chat with historical figures. While the communication envisioned by Mackenzie in these letters may seem to fit such a pattern, it was by no means extraneous to his interest that Levi and Cagliostro were both occult masters from whom more advanced sorts of knowledge might be expected. Mackenzie’s aims here thus partake of a distinctly esoteric form of spiritualism—one that was to flourish in the coming Occult Revival.

Secrets from the Spirit World

Once a promising, Continentally educated young scholar of language and culture, Mackenzie turned in his early twenties to the study of Mesmerism and fringe medicine. Not long afterward, a chance meeting in a bookbinder’s shop with a gentleman twice his age had a profound effect on his thinking. Drawn together, one imagines, by a common interest in the subjects of the volumes they had each brought in for repair, the two men struck up a conversation.

The older man turned out to be one Frederick Hockley, an accountant with an office in the City. In the evenings, he returned to his lodgings in the nearby market town of Croydon, where every Tuesday he communicated with spirits. Mackenzie accepted an invitation to attend one of these crystal-gazing sessions and, as he later related, “a new world of beauty opened upon me.”

This was in the middle of the nineteenth century, when modern spiritualism was spreading throughout Britain. What Hockley practiced was, in fact, an older variety aimed at communing not with spirits of the recent dead but higher beings in pursuit of hidden truths. The tradition can be traced back to John Dee, mathematician, natural philosopher, and advisor to Queen Elizabeth, who with the aid of hired seers spent his last thirty years in conversation with biblical angels and lesser-known entities with names like Ave, Nalvage, and Madimi who appeared in his crystal ball or magic mirror.

Like Dee, Hockley could see no visions himself. Over the course of a quarter century, he had tried out a series of clairvoyant assistants to little effect. Then in 1851, a domestic catastrophe led him to take lodgings with a man whose adolescent daughter turned out to be a naturally talented medium. With her help, he entered into weekly communication with an inhabitant of the Seventh Sphere that he called the Crowned Angel. He made careful records of these conversations and later distilled from them a complete metaphysical system, which he planned to publish in three volumes.

In the June 16, 1875 letter quoted above, Mackenzie—no doubt exaggerating his own role in these experiments in crystal gazing—recalled with pride how he and Hockley “pursued the subject together.” Hockley certainly introduced Mackenzie to the practice and encouraged his interest in the occult more generally, lending him rare books and manuscripts from his celebrated collection of esoterica. After Mackenzie visited his other master—Eliphas Levi—in 1861, it was Hockley whom he rushed home to tell, and notes of the encounter set down at Hockley’s insistence would later form the basis of a celebrated published account. In his letters to Irwin of the 1870s, Mackenzie refers to Hockley frequently and with the highest admiration, though by then, much to his regret, he was no longer on speaking terms with his mentor. Hockley had broken off the friendship several years earlier due to Mackenzie’s alcoholism and insulting behavior when drunk.

By this time, it was Irwin who was enjoying Hockley’s tutelage. He had met him quite independently of Mackenzie through mutual friends, the noted spiritualist Mrs. Everitt and her husband. A retired army officer living in Bristol, Irwin did not get into London often, but after being invited to Hockley’s flat on one such trip in January 1872 he kept up a regular correspondence with his older friend, whose influence on him was soon apparent.

Shortly after their first meeting, Irwin quizzed Hockley about which type and make of crystal ball to buy at what price. The latter replied at length, advising he get one made of rock crystal and beryl rather than common glass, which can be “very fatiguing to the eye.” Irwin did so and began experimenting with the crystal he purchased, his fourteen-year-old son Herbert acting as medium. They soon started to receive a variety of esoteric teachings from scriptural apocrypha to magic spells, and by October 1873 Cagliostro was a frequent interlocutor.

For Hockley, the secrets gathered from the spirit world were a source of enlightenment; it was Irwin who first put them to organizational use. He was after all but a recent convert to spiritualism and the occult sciences, his primary enthusiasm being for freemasonry. Initiated into the Craft at the age of 29 while stationed in Gibraltar, he was known for joining every order and degree within his reach. Lately, he had helped organize no fewer than four new quasi-masonic rites with Eastern or mystical motifs. It is thus no wonder that he picked Cagliostro for a spirit guide as the latter was no mere occultist but the father of esoteric freemasonry.

A Mysterious Brotherhood

In February 1874, Irwin started hinting in letters to his loyal friend Benjamin Cox, borough treasurer for a seaside town in Somerset, that he possessed a connection to a secret fraternity. Sometimes he called it the Brotherhood of the Cross of Light and sometimes the Order of the Swastika (an ancient symbol, needless to say, with no political significance at the time), but it was most commonly referred to as the Fratres Lucis (Brothers of Light).

In time, Irwin let on he had recently been to Paris to meet with fellow members of the order. Cox was soon begging to be allowed to join, and after keeping him waiting for almost a year Irwin saw fit to admit him. Mackenzie was not invited until the following year, and then only upon his solemn assurance that his drinking was under control: “I never drink spirits or wine if I can avoid them—only fourpenny ale.”

When Cox wondered whether there might be any members of the Fratres Lucis then living in Bath, Irwin said no. He could be sure of that, he told him, since “there were only twenty-seven members five years ago,” and “we are bound to keep our immediate Chiefs posted up in all our movements.” Twenty-seven is not a lot, and even that figure may be deceptive. The group’s official history, received along with its rituals and secret knowledge from Cagliostro by means of Herbert’s crystal, declares its members to be “bound by a solemn oath to meet once a year, whether they are living or have passed the boundary.” Death, in other words, does not strike one’s name from the rolls.

Of the twenty-seven members of the Fratres Lucis said to have been claimed in 1869, then, how many were living? They must have made up a distinct minority given that, according to the same source, the order had supposedly been founded as long ago as 1498 and its adepts—“much persecuted by the Inquisition”—had included (and thus presumably continued to include) nearly every prominent mystic born since: Thomas Vaughan, Robert Fludd, the Count of St. Germain, Franz Mesmer, Emmanuel Swedenborg, Martinez de Pasqually, Louis Claude de Saint-Martin, the homeopathist W.H. Schussler, the aforementioned Eliphas Levi, and Cagliostro himself. The entry for the Fratres Lucis in Mackenzie’s Royal Masonic Cyclopaedia (surely contributed by Irwin himself) remarks rather cryptically, “It is a small but compact body, the members being spread all over the world.” Small but compact? Compact and spread all over the world? Clearly we are dealing with a group that transcends not only the laws of physical reality but the ordinary laws of thought.

While the order’s documents speak of branches in Paris, Florence, Rome, and Vienna, its actual members, four in number, divided themselves between London (Mackenzie), Weston-super-Mare (Cox), and Bristol (Herbert and Irwin himself). Irwin seems to have given out that Hockley had joined as well, a claim regularly repeated by those writing on the Fratres Lucis. If so, it is very strange that in the score of letters Hockley sent the Irwins in this period he makes no allusion to the fact.

It is indeed a matter of opinion whether there ever really was a group at all. Despite the formal obligation of members to gather for an annual dinner in June—“the fare to consist of Bread, Butter, Cheese, Confectionary, fruits and wine”—it is doubtful the Fratres Lucis ever met as a body. Rather, it appears to have been yet another fringe-masonic rite organized by Irwin and/or Mackenzie that, in the words of one authority, “existed in great detail on paper, was extensively discussed by letter, but was never actually worked.” And yet the idea of an elite international order led by a shadowy hierarchy of unknown superiors that instructs its initiates in the secrets of the Western hermetic tradition would prove a highly influential one.

Spiritualism and the Occult Revival

Two pioneering organizations of the Occult Revival—the Theosophical Society and the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor—both modeled their legendary history and professed aims to a large degree on those of the Fratres Lucis. Not the least part of this legacy was the use of mediumistic contact with spiritually advanced intelligences—whether living, dead, or never incarnated in human form—as a source of secret teachings. Madame Blavatsky’s came from the far-off and unapproachable Mahatmas, and those of Max Theon from a spirit channeled by a young associate.

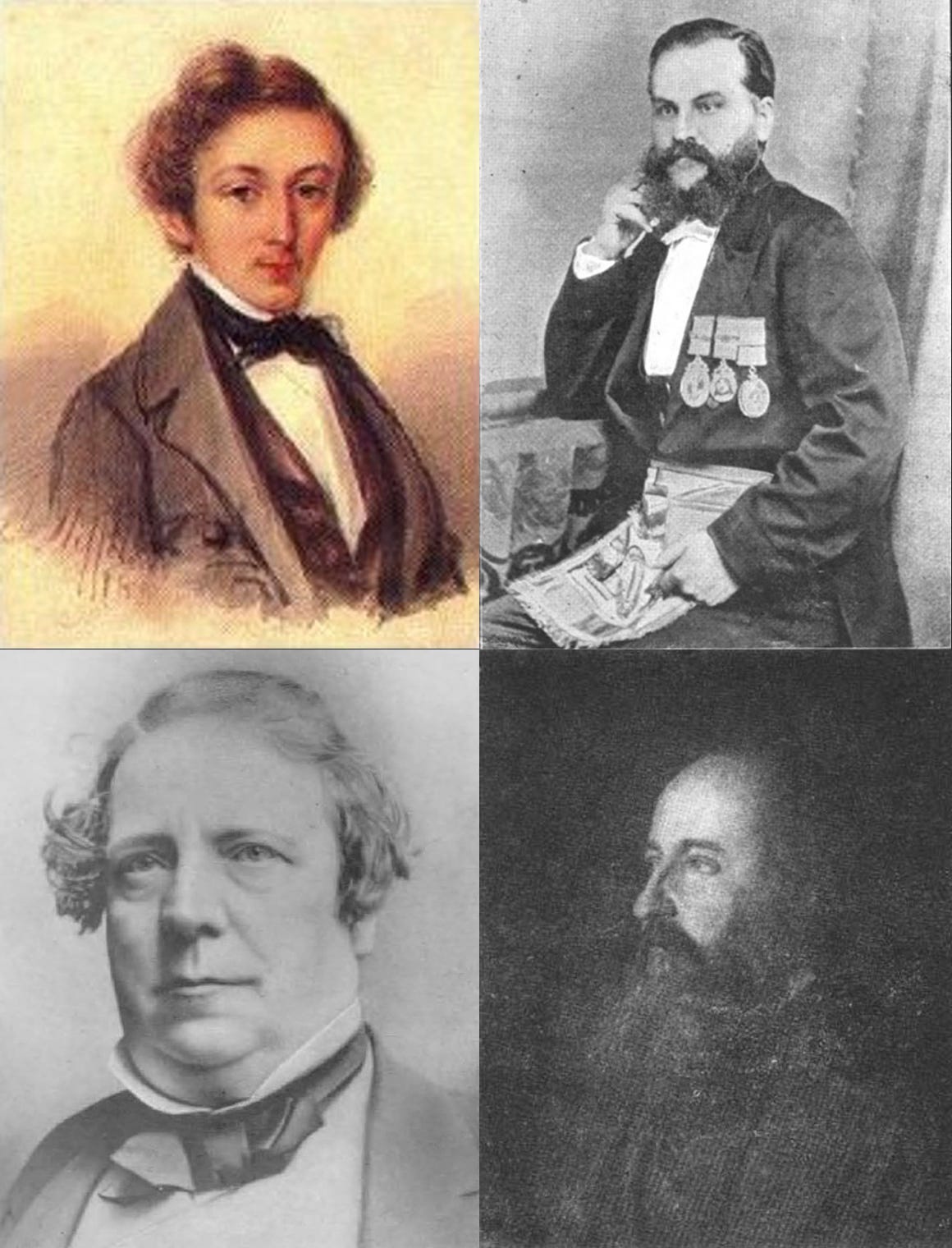

But no society derived more purely from the fictitious example of the Fratres Lucis than the Order of Golden Dawn, which more or less annexed its backstory. The Golden Dawn claimed to be the British revival of a worldwide order of occult adepts much like the product of Irwin’s fancy. This “Hermetic Society whose members are taught the principles of Occult Science, and the practice of the Magic of Hermes,” which like the Fratres Lucis traced its origin to the Middle Ages, was said to have fallen inactive due to the recent death of several eminent members of the prior generation. The opening paragraph of the Golden Dawn’s official history lecture lists these late chiefs of the order, most of whose names the reader has encountered: Hockley, Mackenzie, Eliphas Levi, and another French occult writer from whom Irwin had drawn inspiration. All were safely dead by the time the Golden Dawn was founded in 1888. Irwin himself, who despite having retired from his activity in voluntary organizations was still around to be asked about his relation to the supposedly revived order, is mentioned several paragraphs down as an honored but less direct predecessor. As for Cox, he actually joined the Golden Dawn as head of its provincial temple in Weston-super-Mare.

Like the Theosophical Society, the Golden Dawn officially frowned on spiritualism. To be admitted, candidates had to promise not to “suffer [themselves] to be hypnotised or mesmerised, nor… place [themselves] in such a passive state that any uninitiated person, power, or being, may cause [them] to lose the control of [their] thoughts, words, or actions.” Members were supposed to develop their magical wills and were by no means to surrender them to an alien influence. But the taboo applied only to the invisible entities of modern spiritualism—the spirits of the “uninitiated” dead and lower elemental spirits. Contact with higher beings was quite another matter.

Indeed, the rituals and higher teachings of the Golden Dawn’s Second Order were received from Frater L.e.T., a remote and superhuman Secret Chief, by the group’s Chief Adept—Samuel Liddell Mathers—through his own mediumship and that of his wife Moina. Nor were they the only leading members to engage in the practice. In 1895, Florence Farr made contact with an ancient priestess, Mut-em-menu, whose mummy was on display at the British Museum. Encouraged by Mathers to pursue the communication, she organized a secret group within the order for the purpose. In 1901, after Mathers was deposed in a rebellion against his despotic authority, the nature of the being Farr had invoked, the virtue of its influence, and the desirability of the group she led were at issue in a rancorous faction fight that further shook the order.

As the organization was torn apart over the coming years, three more contacts among the Secret Chiefs would emerge in support of rival claims to leadership: Annie Horniman’s Purple Adept, John Brodie-Innes’s Inner Master of the Solar Order, and Dr. R.W. Felkin’s discarnate Arab teacher Ara Ben Shemesh. In 1907, Aleister Crowley—a dissident from Mathers’ successor organization and the one led by Felkin and Brodie-Innes alike—formed a third, competing group, the A∴A∴, whose holy book had been dictated by a spirit named Aiwass through Crowley’s wife Rose on their extended honeymoon. Perhaps it was in view of these bitter schisms that when various controlling spirits vouchsafed an esoteric system of history to another former member—W.B. Yeats—via the automatic writing of his wife Georgie (starting on their honeymoon), rather than found a secret society of his own he instead composed A Vision and “The Second Coming.”

Lesson learned. Convenient as it may be for leaders of an elite occultist order to resort to spiritualism as a source of exclusive and authoritative secrets, the contrivance is not without its drawback. Namely, there are enough spirit guides to go around.

Sources

I consulted the letters of Mackenzie to Irwin of November 7, 1874 and June 8 and June 16, 1875 in the collection of the Museum of Freemasonry, whose informative catalogue is free to search online. Image at the top of the post: Letter of K R H Mackenzie to F G Irwin, 16 June 1875, MSS 39/3/1/33 ©Museum of Freemasonry, London.

The classic account of British fringe masonry is Ellic Howe’s “Fringe Masonry in England 1870–85” (1972).

Mackenzie’s life and influence are discussed in R.A. Gilbert and John Hamill, introduction to the Aquarian Press edition of the Royal Masonic Cyclopaedia (1987); Joscelyn Godwin, The Theosophical Enlightenment (1994), chapter 11; and the work by Ellic Howe cited above.

On Hockley, see John Hamill, The Rosicrucian Seer (1986) and the work of Joscelyn Godwin cited above. Hamill is the source of the quote on the activities of the Fraters Lucis.

Mackenzie describes meeting Hockley and the latter’s crystal-gazing sessions in “Visions in Crystals and Mirrors,” The Spiritualist, March 29, 1878.

On Irwin and the Fratres Lucis, see the works by Ellic Howe and Joscelyn Godwin cited above. The Theosophical Society and the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor are also discussed by Godwin.

The Golden Dawn’s “Historic Lecture for Neophytes” can be found in the Golden Dawn Source Book by Darcy Küntz. The “Obligation of Candidates Admitted to the Order of the G.D. in the Outer” is included in R.A. Gilbert, The Golden Dawn Companion (1986). See also Ellic Howe, The Magicians of the Golden Dawn: A Documentary History of a Magical Order 1887-1923 (1972).