Early in the correspondence between two noted Victorian students of the occult, Frederick Hockley of London and Capt. F.G. Irwin of Bristol, a message of Irwin’s went astray. Weeks later, a follow-up letter arrived under circumstances that shed light on the fate of its predecessor. As Hockley tells it:

I return your envelope as it explains the miscarriage of your former missive and points a moral ‘that whilst we allow our minds to delve into the Occult and hidden mysteries of nature and science’ or ‘cross the threshold of the mysterious world of spirits’ we must not be unmindful of those little hieroglyphics on brass which distinguish our humble dwellings in this subluminary world. No. 168 is between 2 or 3 hundred yards from 167 on the opposite side of the road, and is in another delivery.

In his forty-odd surviving letters to Irwin and his son, Hockley shows himself to be that rare thing: an occultist with a sense of humor. He even displays a certain irreverence toward the “hidden mysteries” that form the object of his study. The attitude is apparent from the first, when at the suggestion of a mutual friend he wrote to ask Irwin to “do me the honour of a call on Saturday next any time after 5.30 to take a cup of tea and have a gossip [about] old authors on queer subjects.”

In his next letter, he replied to an invitation to join the Bristol College of the Rosicrucian Society of England, of which Irwin was the organizer:

As to the Rosicrucian College, I little dreamed that when my attention was drawn to the Secret Lodge in the East (from which resulted the revelation from the Spanish Monk I read to you) that I should become a member of the Rosicrucian College in the near West [i.e., Bristol], but I should be pleased to join if you would do me the honour of proposing me…. [P]ray send me word what the fees are & I will send a P[ostal] O[rder] by return of post and trust some fine morning to wake up and find myself an Invisible one?

When he reached that paragraph, the more serious-minded Irwin must have grit his teeth.

Hockley’s light-hearted tone belied his devotion to the pursuit of secret teachings. He had been at it since his youth, when he went to work for a dealer in esoteric books and manuscripts with a little shop in Covent Garden. There he read through the entire inventory and started his own fabled collection, which would one day number over a thousand volumes. He also took up crystal gazing at this time. Later in life, with the aid of the teenage daughter of his landlord, he made contact with a spirit guide from the Seventh Sphere whose weekly conversations over a period of years revealed to him many mysteries of life and death.

By the time he met Irwin at the age of 65, Hockley was well known for his occult learning and familiarity with the spirit world—at least among fellow spiritualists and the small circle of esoterically inclined freemasons to which Irwin belonged. Now a partner at an accounting firm in the City, he nevertheless lived alone in inconvenient circumstances and failing health, haunted by an absence that followed him from one rented room to another: that of his wife Sarah, who 23 years earlier had taken her own life.

Irwin, then 45, was a retired army officer leading a volunteer unit in Gloucestershire. He had a promising young son at boarding school in Bath and a respected career in both regular and irregular freemasonry. New to the practice of occultism, he looked up to Hockley and emulated his activities. Over the next dozen years, his life would eerily mirror his older friend’s both in its fanciful achievements and real-life tragedy. The two would spend their later years in desperate search of consolation—and when near the end of his life Hockley finally found comfort for his own loss, Irwin was at his side.

“The use and abuse of Spiritualism”

Soon after their first meeting, Irwin wrote Hockley for advice on assembling his own occult library, which the latter gave willingly and at length: “[The dealer’s] Agrippa is far too dear. I see out of the catalogue you sent me I have got about £60 worth of his books, you will see I have marked mine with little dots….” He even lent Irwin materials from his own collection to transcribe for himself, including copies of rare manuscripts and precious transcripts of his communications with the spirits.

When Hockley recommended he try crystal gazing, Irwin went shopping for a suitable ball. Unable to see anything in it himself, he made use, as Hockley had done, of an adolescent clairvoyant—in Irwin’s case, his 14-year-old son Herbert. While this may seem a taxing role for one so young, bear in mind that at the same age Irwin had joined the army, enlisting as a bugler in the Corps of Royal Sappers and Miners.

With Herbert’s help, Irwin’s efforts soon paid off. Within a year’s time, the two were communicating with the departed spirits of notable alchemists, astrologers, and mystics of the past, among them the eighteenth-century occultist and adventurer Cagliostro. In this manner, they received the text of several arcane manuscripts, including the rather artlessly titled Book of Magic, an illustrated collection of occult teachings with chapters on such topics as invoking angels and demons, divination by dust or ashes, and the secret alphabet of “some famous Cabbalists.”

Impressive as these results may seem, they were not wholly original. When Irwin sent Hockley two works dictated to Herbert by their spirit guides, the latter politely allowed them to be “very curious and very interesting” before going on to complain: “It is astonishing to me that our Invisible Friends do not give us anything valuable and new.” Both manuscripts, he noted, owed much to sources familiar to him, including the apocryphal Book of Enoch and one he had actually lent the Irwins, J. Dupotet’s La Magie dévoilée.

Around this time, Hockley began to take an interest in young Herbert, who was himself reading deeply in occult subjects. He recommended books to him and let him borrow, among other hard-to-find materials, manuscript copies of two medieval grimoires that must have inspired the Book of Magic. In June 1874, he arranged to meet the boy in London. “I look forward to seeing Herbert with much pleasure,” he told Irwin. “I want a long talk with him on the use and abuse of Spiritualism.” Perhaps he intended to caution the boy against putting words from his reading into the mouths of the spirits who spoke through him.

Or perhaps he meant to talk to him about something more serious. The book of occult teachings Herbert received from the spirit of Cagliostro includes a chapter on the magical use of certain drugs and herbs, including narcotics. To induce his visions, he presumably resorted to various stimulants, hallucinogenic compounds, and laudanum—a tincture of opium then widely taken for pain and insomnia. It was likely no accident that his health began to suffer. “I hope this will find Herbert all right,” Hockley writes on August 12, 1874, “& that he has not overworked himself for his examinations. It is vexatious that Spirit intercourse weakens us physically.”

In the event, Herbert failed his examinations, and a halt was called to his crystal gazing for a time. By the following April, at the age of 16, he was nevertheless spoken of as a chronic invalid. “I regret exceedingly to hear so bad an account of my dear young friend,” Hockley writes.

He looked very unwell when here [on a second visit in December] but I was in hopes that would pass off on his return home—it must indeed have been a source of great alarm to Mrs Irwin & yourself and I rejoice to learn he is now improving and will I trust thoroly [sic] recover his health, but he will require great care for some time.

Hockley’s hopes were disappointed. From this point on, Irwin’s correspondents hardly ever mention his son without expressions of sympathy for the latter’s poor condition and wishes for his speedy return to health.

In June 1877, though far from improved (“I am indeed very sorry tho’ not surprised at your having been so unwell,” Hockley writes him at the time), Herbert went off to Paris to study medicine. In January 1879, having just turned 21, he died there of a laudanum overdose.

“It is of no use giving way to grief”

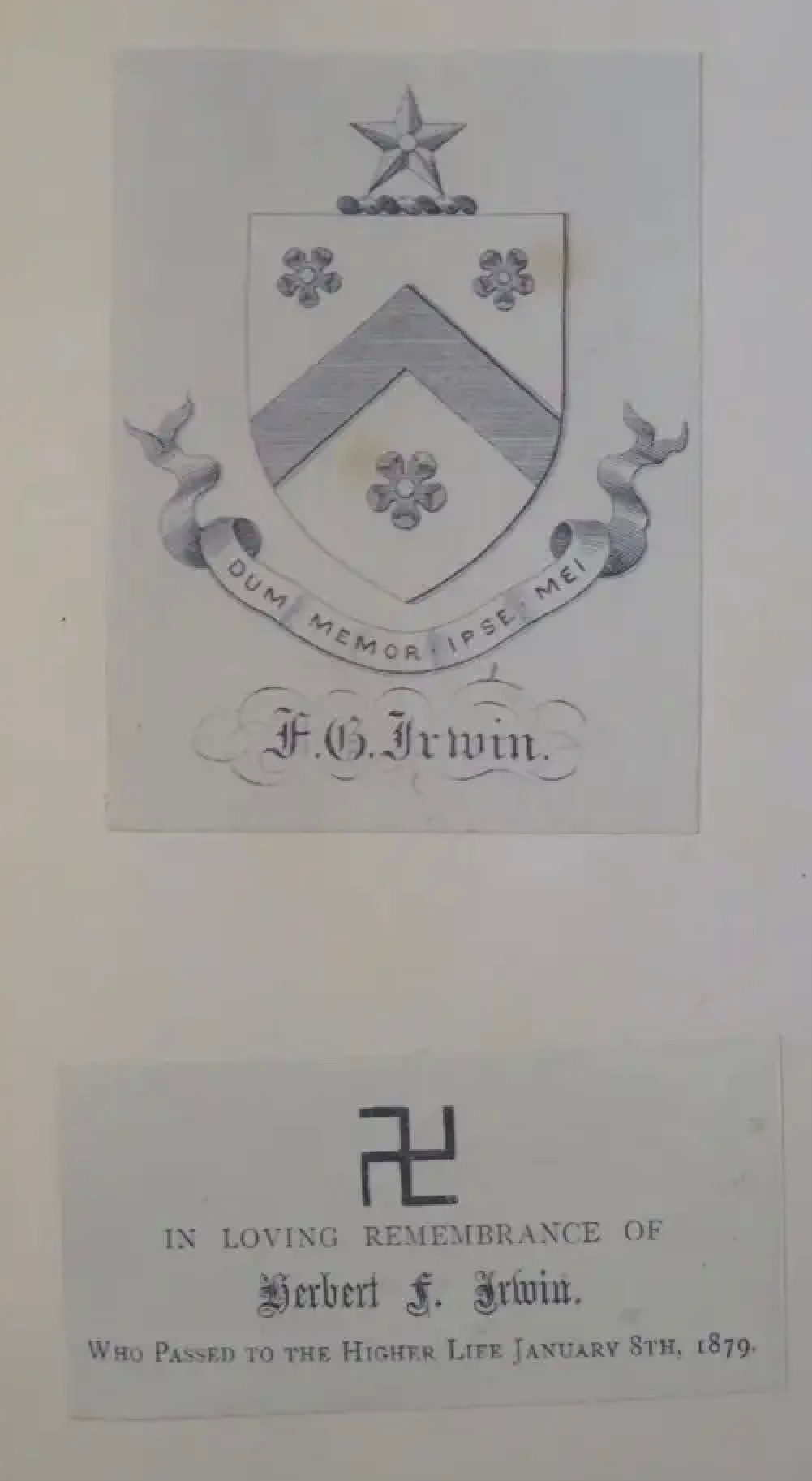

Irwin never recovered from the blow. Herbert was his only child, and the two were unusually close. Besides serving as a captain in the volunteer militia Irwin directed, Herbert was a member of every masonic order to which his father belonged as well as the no less than five esoteric rites he led—including one founded on the basis of Herbert’s own clairvoyance, the Fratres Lucis, which was to have a seminal influence on the late-Victorian Occult Revival and the Golden Dawn in particular. To every volume added to his library thereafter, Irwin pasted a bookplate adorned with the symbol of the Fratres Lucis, a left-facing swastika (the associations of which were then purely Eastern and mystical), and inscribed, “In loving remembrance of Herbert F. Irwin, who passed to the higher life January 8th, 1879.”

Upon his son’s death, Irwin withdrew from all the various voluntary associations—masonic or para-masonic—in which he had been active and addressed himself solely to reaching Herbert in the spirit world. He regularly attended seances with a well-known medium in Bristol, but to his dismay his son could not be summoned.

The failure of these sessions was anomalous. The Rev. William Stainton Moses, a well-known London medium with whom Irwin corresponded, was frankly puzzled. “Your persistent lack of results seems to me one of those surprising things that I accept without being able to understand or explain,” he wrote in 1881, after Irwin had been trying for two and half years. “I think I know four people who are as unfortunate as you.” Such an outcome was only to be expected among skeptics, but Irwin was not of that sort: “I know many who do not care a fig about the theory, many who scout it and scoff, but few who honestly seek without finding.” Moses could only counsel patience and resignation.

Another friend to whom Irwin turned was his old companion in esoteric and para-masonic pursuits, Kenneth R.H. Mackenzie. Mackenzie recruited the assistance of a young medium in Brighton, and Irwin lent him some personal belongings of Herbert’s to draw the shy spirit out. After a year’s worth of unfortunate delays, Mackenzie sent a disheartened report on February 28, 1883: “Herewith I return the necktie and locket of poor Herbert, and at the same time wish to tell you why nothing has been done.” The young lady’s visions, while interesting, “did not admit of departed persons being summoned.” Mackenzie regrets he has no better news, especially as over four years after his son’s death Irwin remains in a terrible state. “I am sorry to hear such an account of yourself,” Mackenzie tells him. “It is of no use giving way to grief.”

When Mackenzie is finally able, in a letter of February 18, 1884, to bring good tidings, they come from a familiar source:

I saw our dear old friend Bro. Hockley on Saturday last and was with him nearly four hours. He talked most kindly about poor Herbert and bade me say when I wrote to you that a seeress has lately been in communication and said that Herbert appeared and was at last happy . . . P. S. Hockley is moving somewhere but I don’t know where yet.

“A cherished communication from his long-departed wife”

Mackenzie’s postscript refers to only the most recent of Hockley’s frequent and unexplained changes of residence. These moves were made all the more difficult by his cumbersome library and ill health, as evoked in a letter to Irwin dated September 28, 1877:

I have changed my residence, & first had to send off my books & cases & the following week my furniture—being utterly helpless as far as doing any thing myself & obliged to depend on others and the wearisome process of putting down carpets, putting up blinds & curtains, & my books piled up all over the room & even now only placed away according to size and not subject—& my incessant pains when moving about….

Some time in 1879, he moved again, falling out of touch with Irwin and Mackenzie for a time. And then on September 16, 1883, Mackenzie wrote to Irwin with a familiar story: “Yesterday came a letter from Bro. Hockley whom I wish to interest in the Society of Eight. He is again on the move with all his Library. He has been ill.”

Hockley’s health had been bad enough back in 1873—as he wrote soon after meeting Irwin, “I have been, ever since I had the pleasure of seeing you here, exceedingly unwell and taking powerful medicines”—and as the years passed it only continued to deteriorate. In the letters, he complains of eyestrain, insomnia, headaches, weakness, prostration, chest pains, and fainting spells. Some of these troubles, at least by his own account, had started in 1850 after Sarah, his wife of 12 years, killed herself in a fit of madness:

For a whole year after my poor wife’s sad death I laid awake with unclosed eyes 1 night, half the next I dozed, the third night I slept soundly, the 4th night awake, and so repeated for more than 1 year but it brought me a severe pressure in the right of the brain & from that, more than 20 years ago, I have never recovered.

By 1883, the motive of his contact with the spirit world had shifted from a thirst for higher knowledge to a longing to hear once more from the loved one he had lost. Like Irwin, he frequented seances with this purpose, and in his case too without success. As Mackenzie reported in February, “I saw Hockley about a fortnight ago—to me he seemed in better health, but is sadly troubled at not being able to get any communication from his wife.”

Hockley’s disappointment would not be relieved until the following year, when he and Irwin visited the famous medium William Eglinton. Eglinton specialized in slate writing—a form of spirit communication in which responses from beyond the physical realm were mysteriously inscribed on stone plates. A long account of the session from Irwin’s pen was received by the journal Light—a popular Spiritualist weekly—in October 1884, though regrettably the editors did not see fit to print more than a couple of paragraphs. From the published excerpt, one learns Irwin carried his own slates to the session in a locked case prepared as an experiment by his local medium, George Tommy. As Irwin tells it,

The box lay on the table in full view; the hands of Messrs. Eglinton and Hockley, and my own resting on the top of the box. While in this position writing was distinctly heard, and upon opening the box and taking out the slates the words “Will this do, Mr. Tommy?” were discovered on the inside of one of the slates.

The passage fails to account for Hockley’s presence at the session. For an explanation, readers of Light would have to wait for the issue of November 28, 1885, which included the latter’s obituary. The admiring notice closes with the observation that Hockley “maintained his interest in Spiritualism to the end, one of his latest visits being to Mr. Eglinton, through whose mediumship he received, in writing between slates, a cherished communication from his long-departed wife, intimating that he would speedily rejoin her.”

The prediction, while perfectly true, was not so marvelous. Hockley must not have looked well. When in a little over a year’s time, at the age of 77, he was found dead in his accounting office, the cause was declared to be “natural decay and exhaustion.”

Irwin followed in 1893 at the age of 65. His widow left his papers to the library of Freemasons’ Hall in London, and so made available the window into the lives, activities, and cultural influence of Irwin, Hockley, and their circle without which this post and several of my previous ones, which are linked above, could never have been written.

Sources

Hockley’s extant letters to the Irwins and passages from Mackenzie’s letters to Irwin making reference to Hockley are printed in John Hamill, The Rosicrucian Seer (1986).

I consulted additional correspondence received by Irwin in the collection of the Museum of Freemasonry, including Mackenzie’s letters of April 13, 1882 and February 26, 1883 and Moses’s letters of February 8, 1879 and September 19, 1881. The museum library’s catalogue has good summaries of the Irwin correspondence and is free to search online.

Irwin’s life and masonic career is detailed in Charles Wallis-Newport, “From County Armagh to the Green Hills of Somerset: The Career of Major Francis George Irwin (1828–1893),” Ars Quatuor Coronatorum (2001).

On Irwin and Herbert’s crystal gazing and the Fratres Lucis, see Ellic Howe’s “Fringe Masonry in England 1870–85” (1972) and Joscelyn Godwin, The Theosophical Enlightenment (1994).

In 2014, a reproduction of Irwin’s Book of Magic was published by Caduceus Books/the Society of Esoteric Endeavor in a highly limited deluxe edition. I have relied on the publisher’s description of this work.

The issues of Light containing Irwin’s report of his seance with Eglinton (October 25, 1884) and Hockley’s obituary (November 28, 1885) are available from the International Association for the Preservation of spiritualist and Occult Publications.