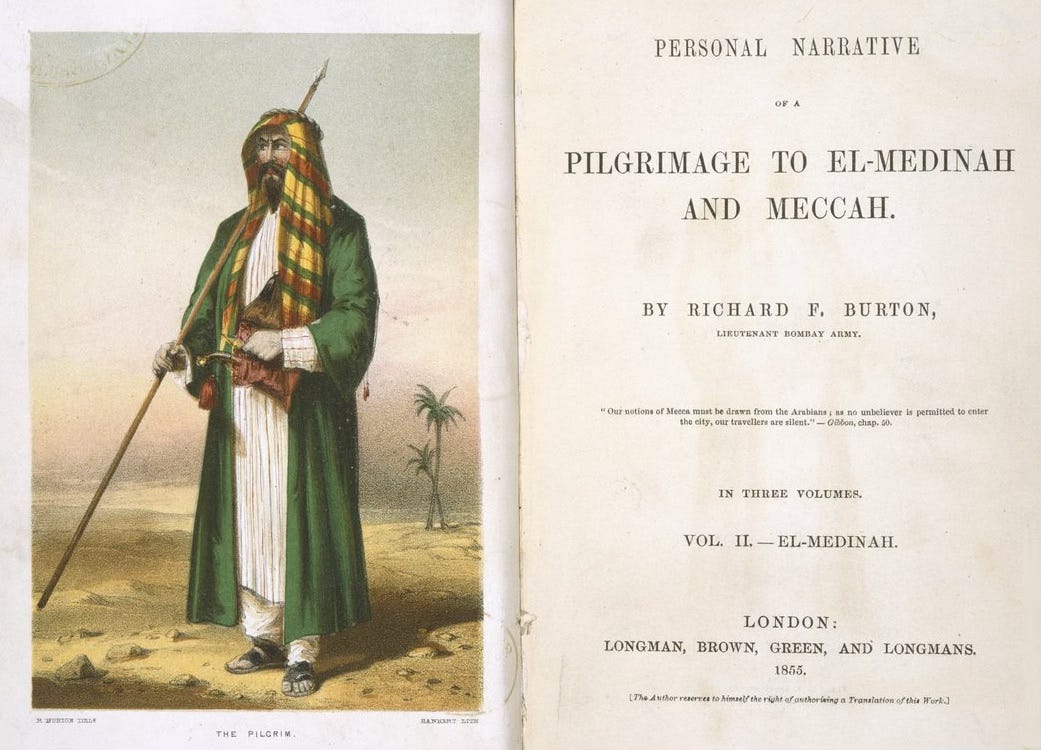

Among those taking part in the mid-Victorian spiritualism craze and the subsequent Occult Revival, Frederick Hockley was a name to conjure with. Celebrated mediums such as D.D. Home, Emma Hardinge Britten, the Rev. William Stainton Moses, and Mrs. Thomas Everitt were friends and colleagues, as was the astrologer Lieut. R.J. Morrison (aka Zadkiel). Hockley corresponded with the industrialist and social reformer Robert Owen, who published the exchange in his spiritualist journal New Existence of Man Upon the Earth. The fourth Earl of Stanhope had a crystal ball made for him, and when the explorer Richard Burton needed one to carry on his journey to the forbidden city of Mecca in the guise of a wandering Sufi magician, it was Hockley he called on. The most notable occultists of the 1860s and 70s—Kenneth Mackenzie, Major F.G. Irwin, and the Rev. W.A. Ayton—counted themselves his pupils, and he was claimed as a progenitor by the Golden Dawn.

Hockley owed his renown to a series of communications held in the 1850s with an entity he called the Crowned Angel and came to consider his “guardian spirit.” In response to over 12,000 questions touching on the mysteries of life and death, this dweller in the Seventh Sphere revealed to him what amounted to an elaborate metaphysical system. Hockley’s transcription of these replies filled 30 notebooks that he kept under lock and key, portions of which he would allow to appear from time to time in various esoteric publications.

But Hockley did not have the knack required to make contact with the Crowned Angel on his own. Instead, he relied on the help of Emma Louisa Leigh, the daughter of his landlord. At the start of their association in 1851, Hockley was 43 and Emma just 13.

Their working method is described by Kenneth Mackenzie, a friend of Hockley’s who was invited to observe it firsthand. “Imagine a quiet room with ordinary furniture,” Mackenzie begins. Hockley would take up his writing materials, and Emma would sit “in a darkened corner of the room, with her eyes fixed upon a silvered mirror.” With “a few words emphatically and sincerely spoken,” Hockley would consecrate the mirror, and before long, Emma, peering into the glass, would begin to speak: “The mirror is clouded, now there is light—now a form appears—describing it accurately—it is so and so.” Hockley would respectfully address the spirit now visible to Emma and ask how it wished to proceed. In reply, words would appear in the mirror “prescribing the question of the night.” These Emma would read off as quickly as Hockley could take them down, and when she came to a stop he would respond in his turn. In this way, every week for a couple of hours at a time, “a conversation would take place upon subjects as sacred as any. Or, it might be, another spirit would appear and the course of inquiry be altered, the freest communication intellectually prevailing.” There was, one is assured, no question of Emma’s putting on a show for some self-interested motive of her own, since “the seeress, a young lady of average education, had a marked antipathy to these mirror evenings—they affected her health, gave headaches, and many troubles.”

The reader may be starting to harbor suspicions, and not merely about the true nature of these conversations. These days a close and private relationship between a middle-aged man and an unrelated adolescent girl may be seen as intrinsically dubious. Moreover, a request by the former for a regular service on the latter’s part—especially one that is unpaid—smacks of exploitation. And then there is the matter of the girl’s stated reluctance to perform this work and its ill effect on her comfort and well-being. Should that not have put a stop to the arrangement, whether she agreed to go on with it or no? And could such assent, for that matter, have been freely granted? The difference in age, sex, and status between the two parties would be hard enough to negotiate today, much less in the Victorian age. This is beginning to look like a simple case of abuse.

I am not going to argue such a reading is impossible. But there is another story to tell here, one I think better fits the facts insofar as they are known.

From this alternative perspective, Emma is less a victim than a virtuoso. A glance at the extant records reveals a varied, inventive, and highly independent improvisation delivered so fluently that Hockley’s pen often struggles to keep up. In their seven-year collaboration, Hockley may have recruited Emma to the task, given her to know what was expected, and prompted her with questions, but the creative force was hers.

Needless to say, this role could never be avowed. At the same time, the truth was not hard to conceal. As a “young lady of average education,” Emma was at least initially presumed to have little interest in or understanding of the teachings divulged by the Crowned Angel. In fact, as in the passage quoted above, the utter improbability that the communications she relayed should come from her was taken as a warrant of their authenticity.

Oddly, their source is still treated as a mystery in the few modern discussions of Hockley available. Commentators merely note it seems unlikely that Emma could have produced material of such sophistication and range, forgetting Sherlock Holmes’s dictum that once the impossible has been eliminated, what remains must be the case.

No one, at any rate, suspects Hockley’s results to be a hoax of his own. His surviving private notebooks, which in his lifetime he showed to perhaps a handful of intimates, bear all the marks of contemporaneous verbatim transcriptions. They are strewn with blanks and misspellings where Emma’s words ran on too fast, here and there amended on a second pass. Hockley would often omit his part in the exchange entirely, trusting himself to recall his own words in a notation made for his eyes alone. And as will be seen below, he recorded his sessions with at least one other clairvoyant, and the difference in outcome is as apparent today as it was to Hockley.

So let us take a look at Emma’s improbable achievement and the light it may shed on the relationship between Hockley and his unseen seer.

Little is known about Hockley’s background, though it has recently been learned that his father was residing at the time of his death in the well-to-do Mayfair section of London. In his youth, Hockley worked in the Covent Garden shop of the occult bookseller John Denley, where he may have copied manuscripts for collectors. He married a woman named Sarah at the age of 28 and some years later joined an accounting firm in the City.

By 1850, he was living with Sarah in the pleasant London suburb of Croydon. At the end of that year, Sarah took her own life; the death certificate states she was of unsound mind. Many years later, Hockley would go from medium to medium in search of a reliable word from the spirit of his beloved spouse.

After the shock, Hockley went away to live with friends in Hackney, but by the latter part of the following year he had returned to Croydon as a lodger in the home of retired excise officer Edwin Wavell Leigh. The street was respectable but socially mixed: neighbors included gardeners, bricklayers, a horse dealer, and the master of a Church of England school for the poor. Leigh had two daughters, of whom Emma was the younger.

Hockley had owned a crystal since the age of 16 but never managed to see anything in it. Over the years, he had tried a number of clairvoyants—“generally female”—and reported a couple of interesting experiences, but on the whole the results had been, as he later judged, “desultory.” Emma seems to have taken to the practice at once, though her skills needed some polishing. As Hockley would later describe the process,

I have had in this instance entirely to develop the faculty of crystal seeing in my young seer, who being at the commencement only just turned thirteen, and the inquiry strange to herself and her friends [that is, her family], I had to be very cautious not to alarm her fears or her friends’ prejudices, and as at first evil spirits kept continually entering our crystal, their ugly faces and forms would have been a source of alarm to many other young persons. Fortunately on spiritual matters my young seer is not the least nervous.

One gathers that Emma’s received idea of how a person’s departed spirit might appear was rather spookier than what Hockley had in mind. They went through three notebooks before she settled on the Crowned Angel, an exalted being whose centuries of progress in the spirit world gave its words an authority that was all but infallible. Hockley was enthralled. As he told Robert Owen, “it was not until the C. A. became my Guardian Spirit that I could bring my experiments to anything like a satisfactory conclusion.”

Owen, once an outspoken rationalist, had late in life taken up the practice of spiritualism. As a test of the value of crystal gazing against other methods such as spirit rapping, Hockley invited him to submit questions to be put to the Crowned Angel. Owen obliged by sending several sets of numbered propositions, and Hockley wrote back with the replies he received. Whatever their value as doctrine, their bold and frequently acerbic tone impresses:

Proposition 1.—‘That the universe is an eternal existence, consisting of space and all within it.’

C. A.—It is not eternal. ‘Heaven and earth shall pass away, but my words shall not pass away, saith the Lord.’ In the words of the most High we have the distinct assurance that the universe is at his will but a void.

Proposition 5.—‘That the element or elements filling the universe, with their inherent unchangeable qualities, are eternal, and constitute “Deity,” or the “All in All” of the universe.’

C. A .—[Owen] does not recognise the Almighty as a distinct and separate power from nature. In that, of course, he is wrong. I cannot help remarking that he is too elaborate in his opinions. Strong opinions more simply expressed, would be better understood.

Hockley’s occasion for writing was to warn his correspondent that a spirit with which Owen then took himself to be communicating—Queen Victoria’s late father the Duke of Kent—was really, according to the Crowned Angel, the earthbound evil spirit of the late Ernest Augustus, the unpopular Duke of Cumberland and King of Hanover. Owen published the correspondence, discreetly blanking out the alleged impostor’s name, but could not bring himself to accept the identification. The Duke of Kent had been an old friend of his, and he felt obliged to pass the latter’s messages on to the palace despite complaints from Prince Albert.

But Hockley was to get satisfaction on the matter. One Tuesday evening, the living spirit of an important visitor announced itself in Emma’s mirror: “Victoria Regina.”

Hockley received her highness, and she came directly to her point: “I very much wish to know whether I am to become a writing medium, as I wish to communicate with my father the Duke of Kent—Owen tells me he has heard him rap.”

Here was Hockley’s chance to clear the matter up. “I have been informed by the C. A. that it is not your Father’s spirit but the evil spirit of your uncle the late King of Hanover that visits him.”

“Oh indeed,” replied the queen, “then I should be very sorry to have anything to do with such things.”

While the apparition of Queen Victoria may have been quick to take his word, the Crowned Angel did not hesitate to contradict Hockley’s most cherished opinions. Through conversations with his guardian spirit, Hockley was persuaded to change his religious convictions, turning from Unitarian to Trinitarian and even coming to accept the Virgin Birth.

Emma traded Hockley’s crystal for a mirror in order to receive larger and more lifelike visions. The good effect to which she used the new equipment is on display in an episode involving Richard Burton. In addition to the crystal ball mentioned above, Hockley had given Burton a black mirror, which was supposed to work something like a live webcam. As Hockley later told the London Dialectical Society, which was investigating the claims of spiritualism,

Lieutenant Burton was greatly pleased and went away. One day my seeress called him into the mirror. She plainly recognized him, although dressed as an Arab and sunburnt, and described what he was doing. He was quarrelling with a party of Bedouins in Arabia, and speaking energetically to them in Arabic. An old man at last pulled out his dagger and the Lieutenant his revolver, when up rode a horseman and separated them. A long time afterwards Lieutenant Burton came to me, and I told him what she had seen, and read the particulars. He assured me it was correct in every particular.

Here is the impressionistic manner in which Emma sets the scene:

Now it is light I see some sand—all sand—now I see some camels one is lying down, the other two standing up there’s a black boy with a tremendous rough wig—he looks like a negro laying down. There’s a tall dark man [i.e., Burton] with a black beard and moustaches, and no hair he’s quite clean shaved [on top], he looks so funny, he’s got some sort of a white dress and trowsers on, and something wound round his waist loosly tied at the side—and something like a knife but no sheath, stuck in something coming from the girdle, it hangs from the girdle—he looks quite white against the black boy, [the boy’s] got a head of hair there’s no mistake about that.

It’s getting plain, there’s sand coming behind them, and a clump of trees more like dried thyme, there are tents, they are very low not peaked—they look as though you would be obliged to crawl in—the tree, if it is a tree, looks like a bunch of dried thyme sticking up above a tent.

Emma seems to have been fond of spinning lively narratives in exotic settings. A recurring character who gave her the chance to do so was a fellow occultist and military officer who refused to give his name; Hockley and Emma christened him Captain Anderson. As Anderson had a mirror of his own, they were able to call him into Emma’s, and often did. First met in 1852, not long after they began working, he described his own intercourse with spirits, including an amusing tale of how he once trapped an imp in a bottle.

The captain went on to serve in Crimea when British forces entered the war after 1854. A couple of his updates from the field, as recorded in Hockley’s notebook, will serve to illustrate their character:

Vol. 7, p. 108: He is so altered, so changed, he’s copper coloured, rough—I am afraid you have not been playing at soldiering by your looks. ‘It’s the weather knock’s me up it is not what I do. How are you. If they had begun fighting in the Spring we should have had the war probably ended, with the loss perhaps of not a great many more men than have died of disease. Yes I am all right now thank you.’

Vol. 7, p. 198: Here he is in uniform. ‘Thank you I am well as can be expected as the ladies say.’ Where are you? ‘Within gun shot of Sebastapol.’ Were you under arrest a little while ago? ‘Being nearly arrested for ever on the 5th at the battle of Inkerman, on the 5th I had advanced on horseback in favour of the Column when some chap singling me out took aim with a revolver. One bullet, perhaps two, went into the chest of the horse—but instead of his falling on his side, as most dead horses do, he fell on his knees or rather fell forward in a heap—the consequence instead of being pitched off and rolling over I continued sitting bolt upright with my legs out on each side, at the same moment two or three bullets whizzed past in the place where my head had been only a moment before. So ludicrous was the aspect I presented and so miraculous was the escape that the men fairly burst out laughing.’

In a letter to a friend twenty years on, Hockley would recall, “I never could learn anything of Capt. Anderson but for a great annoyance he became my favourite companion.” From another letter around the same time, we come to know the interesting facts that Emma’s narratives occasionally impinged on Hockley’s real-life experiences, and that their telling was not always confined to a drawing room:

I truly believe I saw [Captain Anderson] and his sister at the London Bridge Station the night he said he saw me there—only a very small portion of what passed between me and Anderson has been recorded by me because we used to [illegible] with him in Lord Ashburton’s Park in the [illegible] & consequently did not keep any record.

One time in 1856, Hockley attempted to call up the Crowned Angel for another edifying discourse, only for Emma to announce, “Here is yourself come in.” Hockley, annoyed, proceeded to engage in the following banter with his own “atmospheric spirit,” a kind of ethereal double, who exhibited a certain irreverence for the project at hand:

QUERY. Why have you come uncalled? Are you the interesting and instructive vision I requested?

REPLY. I am obliged to take any opportunity of appearing, and come when I can. You never ask me. I cannot appear in the other mirror, but when there is no vision I can tell you or show you where you can see me.

Q. Was it you then, who caused this mirror to appear just now, with some reading we could not make out?

R. I caused it to be done.

Q. Can you tell how it is my seer can now read your answers, and yet could not read in the [mirror consecrated to the Crowned Angel]?

R. I suppose because I am not so purely spiritual. Ha! Ha!

Q. I have received from my good spirit friend [i.e., the Crowned Angel] some valuable spiritual information, which I also hope you will study and profit by.

R. You are a prodigy. If you are as fond of telling others what you tell me, and circulate the report of receiving such wonderful information, you are quite entitled to one of those paragraphs in the newspapers, headed, “Wonderful! if true.”

Q. I am going to publish the book [of the Crowned Angel’s revelations] this month, and as I hope you will be greatly benefited by its perusal, just hand me over ten pounds towards the expense of printing.

R. I could tell you how to get it, at least a friend of mine could. He can appear in a bottle of water, and leave a diamond at the bottom worth a great deal more than that.

No survey of Emma’s accomplishment would be complete without a glance at the rhetorical heights to which she could rise. The four-page discourse from which the following passage has been taken was contributed by one “F.H.” to an esoteric journal with the note that it was delivered by “an inhabitant of the Spiritual Spheres, upon the 6th of October, 1857,... between 7.30 p.m., and 9.20 p.m.”:

Spirit, who art thou, and where? The universe answers us—matter of the earth says, “here”: every object in creation speaks of its presence, the minutest part of nature is its habitation, its father is God, and its birthplace, Heaven; and this universal existence that pervades all space—that keeps the earth on its axis, keeps one atom of material to another atom, keeps the sea and the land apart, that makes the green leaves of the oak spring from the brown seed of the acorn, that makes kind produce kind from the infinite to the great through every generation, that never errs, never fails in its system of progress through the most minute subject that makes the same little flower raise its head yearly to the genial warmth of the summer sun, and be of an unvarying hue;—this same Power speaks in the thunder’s roar and the lightning’s flash, is electricity and odic force, is heard in every sound, harmony, and discord that thrills through space, is seen in every colour, and smelt in every perfume, and is the same as the great incomprehensible body that constitutes the inner life of man, intelligent being of another sphere, the angels higher, and still further on the Seraphim and Cherubim above them, and chief of all is the nature and body of Him who is the Creator of it.

Emma reported her crystal gazing was a strain, and indeed it may have been, as creative work so often is. Or the claim may have served, as it does in Mackenzie’s account quoted above, as a guarantee that she had nothing to gain from her performance. In any case, it is difficult to believe the pursuit held no satisfaction for her. Far from showing any sign in the transcripts of reticence or fatigue, she instead recalls Scheherazade drawing out her tales (perhaps as translated by Burton) from night to night.

This impression is particularly hard to avoid when reading of a strange intrusion in the last days of 1856. Hockley was then resolved to put the finishing touches on his exposition of the Crowned Angel’s cosmological scheme when Emma happened to pick up an unconsecrated crystal that had been left on the table in front of her. “It is thick,” she said. “There is a vision in it.”

In the little glassy sphere resting in her palm, she made out an illuminated book lying open for inspection. As the letters on the richly adorned title page were not Roman characters, she could not identify them except to say, “Two or three look like ducks with their heads under water.” She copied out the rest of the design, and by and by a translation was offered: “SPIRITS OF THE SUN, MOON, AND STARS; THEIR TALISMANS AND POWERS,” a work of sacred Chaldean magic.

Such themes were not entirely new in their work. Emma had from time to time received instruction in practical occultism from the Crowned Angel or other spirits, often accompanied by earnest warnings not to make use of it. Hockley had by late 1856 collected these spells and ritual workings in an illustrated manuscript titled Clavis Arcana Magica. It lay on his desk, as a matter of fact, when Emma received these new pages that betokened the revelation of a complete work of this sort.

The following week none other than a seventeenth-century Spanish monk showed up in Emma’s mirror. It was he who had written the book Emma had seen, having discovered its contents by communing with spirits in the same manner as Hockley. Accused of sorcery and put to death by the Inquisition, he managed to safeguard the secrets he had learned by concealing the book on his person as he was burned at the stake. In this way, he carried it with him into the next world. So that his efforts should not have been in vain, he now offered to make the book’s contents known to Hockley. Busy as he was, Hockley could not say no. The manuscript began to appear in the mirror a page at a time, which Emma would copy in pencil and later recopy in color. And so their work together might have gone on and on.

But it was not to be. “Unhappily,” Hockley recounted years later, “my seer’s health, and her subsequent death, precluded her from copying more than a small portion of the work, and we had no further verbal communications with the monk.”

Emma died at home on September 28, 1858. The cause was pulmonary tuberculosis, from which she had suffered for nine months. She was twenty years old. Hockley was present at her bedside and gave official notice of her death.

I have so far considered Emma’s performance from her own point of view. To Hockley, it was necessarily invisible—a diamond deposited in a bottle of water. In his eyes, Emma was no more than a medium, one specially suited by her age and sex to be a passive receiver of light from another world—albeit a highly sensitive, sincere, and adventurous one.

At the same time, there are hints of a deeper relationship. I have noted their outings to Croydon’s Ashburton Park, which could not have entirely been taken up with news of Captain Anderson’s adventures. Another clue, I believe, is their shared interest in ceremonial magic, as witnessed by the reception as early as November 1853 of an operation to invoke spirits and command them “by the power of Evil” to produce the illusion that incinerated flowers have been restored from their ashes. This is an odd thing for a middle-class Victorian girl of 15 to invent. Emma must have been reading deeply in Hockley’s legendary library to come up with a plausible ritual—complete with mysterious magic seals—that was not merely cribbed from a recognizable source.

The reception of the monk’s book—cut short though it was by illness and death—seems to mark a new level of confidence in this regard. Emma now worked alone with no prompting from her collaborator, who was apparently left to look on as she made like she was copying the text of an invisible original. That she had set herself the task of concocting an ancient Chaldean grimoire out of whole cloth demonstrates at once the depth of Hockley’s influence over her and her independent mastery of the material to which she had been led. They were fellow adepts by now, whether he realized it or not.

The only direct evidence of their personal relations dates from October 5, 1858, eleven days after Emma’s death. In a series of four sessions that month, one more a year later, and a sixth in early 1860, Hockley called up Emma’s spirit at the Islington home of his friend and fellow accountant Henry Dawson Lea through the mediumship of Lea’s wife Charlotte.

Hockley’s first question to Emma registers surprise. “As you had such an objection to appear in your lifetime,” he asks, “how is it you have now done so?” It would seem the possibility of her returning in this way had been raised as she lay dying, and she had ruled it out. No doubt she had reason to believe any message passed on in her name would not be her own.

Now she seems to have changed her mind. Indeed, she has changed in other ways too. When Hockley speaks of his pity and grief (“May I ask, dear Emma, if in your own present state you remember the sad sufferings you underwent before death, and the anguish it occasioned us?”) and wonders if she received any comfort from the fond remembrance she had received (“Are you aware that we buried you at Norwood and the stone and your favorite flowers we placed upon your grave?”), her responses are conventional and brief. When he inquires, “Can you favour us with any information which will increase our spiritual knowledge?”—hoping perhaps to continue their investigations under different circumstances—her reply is evasive. He even asks after “our friend Mr Anderson,” but again the answer is disappointing: “I cannot inform you of this subject for he has never once entered my mind.” Emma’s chief concern, oddly enough, is to have a small gift—a drawing she once made of the Crowned Angel—presented to the Leas. When Hockley has trouble putting his hands on the item, she scolds him at subsequent meetings for neglecting her wishes and delaying her long passage through the spirit world to her final rest.

Only in their second-to-last encounter, not long after the first anniversary of her death, does Emma display any real feeling for Hockley, and when she does it is not tender. As a matter of fact, she announces she is appearing to him only under compulsion. She laments her “folly” and “wickedness” in life. “Yet to all outward appearance I was what may be termed good,” she remarks, “think to what an end that fatal ambition lured us on to.” She offers to say more, but as Hockley does not ask her to, this tantalizing outburst must remain obscure.

Had they planned some daring project of which the Leas had been told? One can only speculate. What is plain is the anguish provoked by her words. “My dear beloved Emma,” Hockley replies,

I grieve to hear what you tell me; since you have been lost to me I have been very ill, and from my present seer’s uncertain health, our removals [soon after Emma died, Hockley moved out of her father’s house, and may have moved again since] and other matters, my opportunities of communicating with my Guardian Spirit has been very limited and the loss of that has indeed made my evenings a sad blank. Deeply have I regretted, dear Emma, your having been taken from us.

In another session at the Leas the following month, Hockley lays bare his heart to his guardian spirit:

I wish to observe, and I do as a relief to my mind, that I have been very much hurt at the responses I have received from my late dear seer which, since her decease when referring to me, has been so unkind; and considering her devoted attachment to me when alive on this earth, I feel it acutely. At the same time to my friend Mr and Mrs Lea, although comparatively strangers to her, her responses have been the reverse.

Apparently failing to draw the obvious inference, Hockley continued his sessions at the Leas. Yet he remained discontent, as can be seen nearly half a year later when Emma is called up one last time. He hopes she is happy; she assures him all is well.

Then he asks her about something that has clearly been troubling him. He suspects the “present Crowned Angel” with which he has been communicating by way of Mrs. Lea is not the same one who used to appear to Emma. It no longer seems like the spirit he knew. Indeed.

Sources

On Hockley and his work with Emma Leigh, see John Hamill, The Rosicrucian Seer (1986); Joscelyn Godwin, The Theosophical Enlightenment (1994); Invocating by Magic Crystals and Mirrors, with an introduction by R.A. Gilbert (The Teitan Press, 2010); Clavis Arcana Magica, ed. Alan Thorogood (The Teitan Press, 2012); and Metaphysical Spiritual Philosophy, ed. Alan Thorogood (The Teitan Press, 2018), where Hockley’s communications with Emma’s spirirt are collected.

Their working methods are described by Kenneth Mackenzie, “Visions in Crystals and Mirrors,” The Spiritualist, March 29, 1878.

New details on Hockley’s life can be found in Crystalline Accountancy: Some Notes on Frederick Hockley (1808-1885), a post on the curator’s blog of the online Emma Hardinge Britten Archive.

Eleven volumes of Hockley’s records of his crystal gazing sessions with Emma Leigh were donated by Harry Houdini to the Library of Congress and are now available online.

In Frederick Hockley's ms. 'A Work of Angels & Spirits which have appeared in my mirror and cristals' in the LOC collection there is, as you may already be aware, a pencil drawing inserted in the last page (page 411 in the pdf) ,created one suspects by Emma Louise Leigh, of the Crowned Angel. Perhaps the very drawing that Charlotte Lea was importuning FH to give to her? Looks like he kept it for himself.

In any case FH's words that ELL 'could not possibly have understood' the content of the visions coming through during the 'Mirror Evenings seems unlikely indeed, without in any way diminishing her unique faculties of seership and symbolic vision into the Mundus Imaginalis.

This entry in the transcript of Vol 13 is dated May 4th 1858.